MARIANNA CHAROUNTAKI TO GULAN: there are a series of pressing and pertinent considerations that are shaping the formulation of EU-KRI bilateral relations

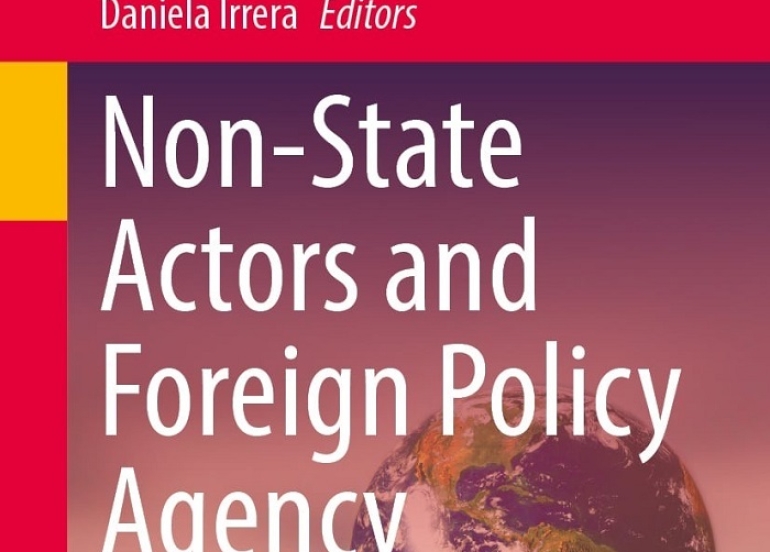

Marianna Charountaki is Senior Lecturer in International Politics at the University of Lincoln (School of Social and Political Sciences). She has acted as Director of the Kurdistan International Studies Unit (2016-2019) at the University of Leicester. She is a BRISMES and BISA trustee and co-convener of the BISA Foreign Policy Working Group. She is also Research Fellow at Soran University (Erbil, Iraq). She has worked as consultant at the Iraqi Embassy in Athens (Greece, 2011-2012). Marianna has been researching the Middle Eastern region, in light of IR discipline, but also through extensive field work research (2007 to present). Her research lies at the intersection of IR theories, foreign policy analysis and area studies with an emphasis on the interplay between state and non-state entities as well as the latter’s conceptualisation and foreign policy standing. She is the author of the monographs The Kurds and US Foreign Policy: International Relations in the Middle East since 1945, (Routledge, 2011) and Iran and Turkey: International and Regional Engagement in the Middle East (I.B. Tauris, 2018) and co-author of Mapping Non-State Actors in International Relations (Springer, 2022). She has published articles in Harvard International Review, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, International Politics Journal, Third World Quarterly, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies and others. In a written interview revolving around her recent article: “Institutionalising Foreign Policy-Making between Non-State Actors: From Reactive to Proactive Relations between the EU and the KRI.” in Non-State Actors and Foreign Policy Agency: Insights from Area Studies. March 2024, pp. 65-81. she answered our questions as the following.

Gulan: What is the overriding principle and philosophy of the EU policy towards Kurdistan Region? and in your assessment is it fair to say that EU has formulated a fully-fledged foreign policy Visa-Vis this Region?

Dr. Marianna Charountaki: Overall, the EU’s foreign policy is in progress given its ongoing attempts to unify its second layer. This is not the case only in the foreign policy field but also in those of both defence and security. Bearing in mind that the institutionalisation of the EU’s foreign policy is a relatively new enterprise –there is, still, a conflict between the Union’s decision-making and the policies of member states, which explains the EU’s country-based approach to policy. It therefore becomes complicated to discuss any supremacy of philosophies that identify intricate relations between the KRI and the institution of the EU as two different types of non-state actors. Thus far, such duality can be seen in the Union’s foreign policy in response to the ongoing crises. If the rise of IS (2014) facilitated EU policies in Iraq, the Kurdistan Referendum in 2017 and its aftermath marked a shift in the EU’s foreign policy. This period seems to have prompted the consolidation of the EU’s presence in the KRI and the beginning of a declared EU Kurdish policy.

Today, it is evident that EU’s interactions with the Kurdistan Regional Government have taken on a more traditionally bilateral form – beyond the humanitarian scope and the EU’s established will to assist in conflict zones. Through engagement at the Union level, direct representation both within the EU and in Erbil, and through regular meetings based on a recognition of the KRI, the EU has shifted from ambiguous foreign policy practices to an interactive and collaborative foreign policy. This willingness to acknowledge and work alongside other non-state actors is evident, in part, through the meetings between the European Union and Iraq since 2015.

Gulan: As you have pointed out the increasing engagement of EU in Kurdistan Region have been driven by some dramatic developments, what is your perspective about the prospect of these relations, are they about to solidify, or we will witness a slowdown in the pace of these relations?

Dr. Marianna Charountaki: At this point, there are a series of pressing and pertinent considerations that are shaping the formulation of EU-KRI bilateral relations. The EU’s foreign policy continues to represent a synthesis of attitudes and perceptions between the institutionalised layers of the EU and the member states’ interests. Also, the EU foreign policy relations are and will be dependent, by and large, on their own capacity to act more decisively and coherently moving forwards. Its ad hoc, two-speed approach, and the domination of prominent member states’ foreign policies, draws into focus the active role of the KRG towards a more active than responsive EU strategy in Iraq.

These priorities mark a transition towards a clearer policy in relation to the KRG. Material structures such as these are reflected in ongoing developments, which explain why the KR is an important actor in the EU’s institutionalisation processes in the field of foreign policy. The question is, therefore, related to the extent to which the EU’s CFSP (Common Foreign and Security Policy) can be transformed from reactive to proactive, and whether its’ will for flexibility – in view of its collective decision-making process – can elevate, further, its relations with the KRI. Such matters encompass EU’s concerns about energy access and counterbalancing Russia’s role in Iraq, as well as the rising Chinese interests, and the role of Iran in Iraq.

Gulan: To what extent EU can play a positive and constructive role with regard to Erbil-Baghdad relations and the resolution of their issues?

Dr. Marianna Charountaki: Despite the recent EU’s statement about the need for the implementation of Shengal’s (Sinjar) Agreement, the EU’s approach to Iraq has been mainly holistic, supporting Iraq’s unity – under its current form of federation – and balancing the forces of both Baghdad and Erbil in light of the latter’s constitutional recognition. It therefore appears difficult for any external actor, let alone a collective entity that represents “Western” interests to mediate in today’s Iraq, other than exerting pressures. The EU has not proven particularly successful in this role when its long-standing mediation in the case of the Palestinian Issue is considered or its more recent response to the Gaza crisis. The EU’s only recent intense political presence in Iraq, beyond the Arab-Israeli settlement, underscores the rising importance of the region for the Union’s foreign policy agenda but equally its’ capacity (based on the level of its determination) to act independently given its’ importance as a significant actor. However, the case of the historically unsettled relationship among Kurds and Arabs (Sunna and Shiites) seems that can be only resolved domestically.

Gulan: What EU and Kurdistan actors should and could have done differently to consolidate and increase their relations?

Dr. Marianna Charountaki: The Kurds and their relations with the states that comprise today’s Union pre-date the Union’s formation as a unitary actor and a contemporary institution. Undoubtedly, the example of French Kurdish policy stands out as an opportunity for the EU foreign policy to act more decisively and coherently toward the KR given the fact that France has acted as a facilitator of Middle Eastern relations, informing the EU’s formulation of a foreign policy approach towards the KR. Indeed, the KRG’s turn to the European Union as the sole interlocutor in the aftermath of international reactions to Kurdistan Referendum in order to advocate for the normalisation of the KRG’s federal status explains the EU’s importance in the KRI’s foreign policy agenda.

Inheriting the good practices of the past and given the most recent direct shift in the EU’s reactions to the political developments in the KR, a changing pattern of behaviour starts to be formulated. A clear EU vision and the converging of individual state’s interests will determine the role that EU can take – departing from the management of recent crises such as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. The EU’s foreign policy interests in Iraq should, thus, uphold international law and human rights alongside the principle of self-determination – a basic Wilsonian principle. A successful EU foreign policy to date would also need to recognise the realities on the ground, as in the case of Iraq, and that each Middle Eastern framework of relations is different. As such, the application of a wide-reaching EU regional strategy would not be adequate (as was the case with the rise of IS when both Syria and Iraq were primarily understood within a single framework) and may be problematic for future policies. Instead, a perspective that maintains the EU’s ad hoc relations with the KRG without these being overshadowed by the emphasis on Iraq’s primacy – given the KRG’s equal constitutional importance – can give the EU an opportunity to expand and consolidate a unified foreign policy that runs in parallel with Baghdad.