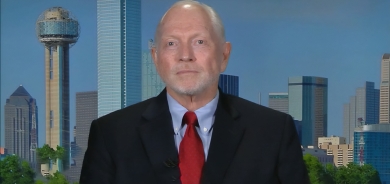

Gulan Media Exclusive: Expert Larry Catá Backer Discusses Challenges to Democracy, Cultural Responsibilities, and Constitutional Law in Kurdistan

In this exclusive interview with Gulan Media, Professor Larry Catá Backer, an expert in company law and cultural relations, addresses the challenges faced by the democratic system in the 21st century, focusing on weakening governance and the impact of societal and cultural changes. He also discusses the significance of constitutional law of religion in fostering unity and tolerance among diverse religious communities. Moreover, he emphasizes the importance of local constitutions for autonomous regions in a federal country like the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

Professor Larry Catá Backer is a Cuban-American expert in governance-related globalization issues and constitutional theories. He focuses on corporate social responsibility, regulatory governance, and the constitutional law of religion. He teaches courses on these subjects at Penn State School of International Affairs. With extensive publications, he is a member of several legal organizations and serves on various journal boards.

Gulan Media: To what extent does the weakening of governance and the challenges posed by societal and cultural changes contribute to the difficulties faced by the democratic system in the 21st century?

Professor Larry Catá Backer: An excellent question: there has been much talk recently about weakening governance, which, together with challenges posed by societal and cultural changes, are said to contribute to the difficulties—some would say the crisis—of liberal democracy. And, indeed, there is a point to that general sentiment about may appear to be a crisis in liberal democracy. One has witnessed the instability in governance, even among apex liberal democratic states. This has manifested itself in what some call attacks on the structural foundations of democratic government. A great example are efforts in Europe and some parts of the Levant to restructure the role of the courts and their relationship of the court to the legislature or the executive. But it has also manifested itself in what some describe as substantial corruption of elections—the core foundations of democratic legitimacy in liberal democratic states. Certainly the enemies of liberal democracy, and advocates of competing systems—including from the Marxist-Leninist and post-colonial camps have made much of this instability—drawing conclusions that suit their own agendas. And certainly, as well, that one can lay the blame for this instability squarely on the inability of elites in liberal democracy—who should all know better—to control themselves. Indeed, one can as easily conclude that the social and moral corruption of those with the heavy responsibility of leadership, rather than the contradictions of the system itself, that may explain the current, and likely temporary, decay in the operation of liberal democracy.

Corruption and decay, however, are the eternal problems of any socio-political system. And all systems must face the inherent contradictions in their translation of theory to actual practice in every generation and in each stage of historical development. The danger here, of course, is that unconfronted, those corruptions, that decay, the self-absorbed decadence of those charged with leadership, and the contradictions that all of this illuminates, can be fatal to a system. It is in this sense important to remember that the heart of liberal democracy was once first Roman and imperial, then tribal and feudal, and then monarchies that once that system developed fully its absolutist tendencies was swept away by bourgeois liberalism that only later matured into classical liberal democracy. At the same time, core civilization values endured, even as they were manifested in each stage of development quite differently—vox populi (the popular voice), lex (law in its broadest sense), respect for popular customs and traditions, and structures of representation (crude versions of what in Marxist Leninist systems is sometimes understood as a mass line). In this sense, even if the current manifestation of late 20th century liberal democracy is swept away, its core values will endure. The same process may be observed with other systems as they have changed from their origins to their present condition.

The second aspect of the question, the role of societal and cultural changes, may help explain the causes and trajectories of these changes (rather than the destruction) of the core values within which states now liberal democratic may express their structures of governance. The state of societal changes have always been tumultuous in what are now liberal democratic states, as they are in most others, to with substantial effects on taste for governance and expectations of the state. However, the rate and trajectories of those changes have been especially acute since 1945. These changes have been blasted across the pages of the popular press, and over the last half generation through social media, so that one has a much greater sense of the changes and their impact in real time. That is something new—the constancy of change less so. Migration has played a role in the changes. But that has been a deliberate policy of liberal democracy—and in the long term a quite valuable policy for reshaping liberal democracy so that what emerges is compatible with the cultures from which all migrants originate (and reflecting to some extent their values in liberal democratic variations). But first a period of turbulence is required, and also one of assimilation, contestation, and reformulation. President Obama famously spoke more than a decade ago to the ideal, then already decades old, of the United States as transforming itself into a representative blending of world cultural and socio-ethnic groups.

One notes the turbulence in the current stage of the historical development of the United States as an apex liberal democratic authority. But turbulence—like abuses of the structures and working styles of liberal democratic governance—can cause weakness. And that weakness can be exploited by those with a different vision of the way that governance, social and cultural matters ought to be arranged. At any rate, the weakness of a system during a period of great change does permit competitor systems the advantage of a space for expanding their own alternative visions. This is especially apparent in the expansive efforts of (Chinese) Marxist Leninist systems through the Belt & Road Initiative and the new Chinese internationalism. But one notes this as well in the efforts of theocratic systems, especially in the dar al islam, to reshape governance, society and culture and to offer that as a model.

But perhaps there is another way of looking at the issues of governance weakness, societal and cultural changes, and the resulting crisis for a political order (in this case liberal democracy—but it could be any). Let us consider this question from the perspective of ‘asabiyyah ( عصبيّة)—group feeling or social cohesion first developed in its modern form by ‘abd ar-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldun in the 14th century (8th century A.H). And, indeed, the crisis in the dar al Islam at the time of the conquests of Tamburlaine, the period when ibn Khaldun wrote, suggests that much can be gained by comparison. The fundamental understanding of ‘asabiyyah can then be contrasted with the Western notion of solidarity as a sociological and a theological concept.

In one sense one can argue that the United States, especially, but more generally many liberal democratic states, are now in the period of decline when the strength of the ‘asabiyyah that produced the great power and authority of the state and its system during the earlier period of its development is dissipated. It may be that liberal democracy has reached a stage of what ibn Khaldun refers to as senility. Yet ibn Khaldun also noted that the dissipation of ‘assabiyyah in one place creates a space for the resurgence of ‘assabiyyah in another place. And that may well be what is now happening during this period of change. This is also captured by the Western concept of solidarity. Solidarity is sometimes understood in three senses: (1) first as a form of ‘assabiyyah among people especially in the form of a natural or voluntary inter-connection; (2) second solidarity is understood as the set of responsibilities that are produced by this natural or voluntary connection with others; (3) third, solidarity is understood as the manifestation of the core values around which it is possible to recognize a group and its core values. In the case of liberal democracy, it is possible to understand that what is now occurring within liberal democratic states is a shifting of solidarity as both the scope of interconnection (and its membership) change and as that change produces changes in the responsibilities of this group, but around the unchanged core values which give the group its distinctive shape.

Gulan Media: As an expert in company law and cultural relations, what does it mean when companies discuss their cultural responsibilities? Additionally, in a multicultural company, which culture is prioritized or takes precedence?

Professor Larry Catá Backer: This is a great question. The short answer is that the relationship between companies and “cultural responsibilities” is a relationship in search of a consensus. And for the moment that consensus appears to be quite elusive. I will briefly consider the way one can approach an answer depending on what one means by corporate cultural responsibilities.

First, the term can refer to corporate cultural competence in relation to its internal operations, its customers, suppliers, or its operations, especially when any of these take place outside the home state of the enterprise. Companies whose operations extend beyond their home state have for many years worried about cultural competence in their operations. This touches on everything from product names (e.g., the famous case of the Chevrolet model “Nova” which when exported to Spanish speaking states exposed a secondary meaning in Spanish—no va means roughly that it doesn’t run) to customs and business behavior norms among employees, customers, and partners. In a sense, this is corporate cultural responsibilities as a form of economically driven cosmopolitanism. There is an element of chauvinism corporate cultural competence; power may be evidenced in the capacity of the foreign corporation to assimilate local culture without any expectation that local stakeholders will develop cultural competence beyond their own.

Second, the term can refer to corporate cultural sensitivity in its internal operations. In this sense the enterprise conforms its operations to local conditions, customs, and expectations, even when these may offend in profound ways, the cultural and social expectations of society in the home state. Much of this conforming is neutral in a cultural sense—pay, working conditions and the like. But some of it does impact—gender segregation, minimum ages for work, housing, medical care, and the provision of other services. Multinational corporations have tended to adapt to local conditions. Cultural sensitivity may also have a legal basis in the form of the law of the home state that legalizes certain key cultural expectations or practices. Cultural sensitivity may be driven by economic factors as well.

In its third sense, the term can refer to corporate cultural compliance, especially with global hard or soft law or norms, and sometimes with the extraterritorial rules of its home state. It is in this sense that much of the current controversy revolves. Let us consider each in turn. Where compliance is required because of the application of the national law of the home state, the corporation will prioritize the application of those rules over the expectations of host state expectations. This has been occurring for over a generation—and the template in the modern sense perhaps can be traced back to efforts such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (bribery). Today, it is marked by two sorts of compliance based legislative efforts. The first consists of sanctions based rules. These limit the ability of enterprises to deal with specified states, people or enterprises, but relating sometimes to issues of political-cultural difference or conflict (for example, ISIS in the MENA region). The second consists of rules, sometimes sanctions based, that forbid either practices (e.g. the national Modern Slavery Laws of the UK, Australia, Canada and others) that may otherwise be tolerated in host states. That toleration may arise because of cultural differences, or for less positive reasons (capacity, control, etc.). A variation of these norms based national rules has emerged in recent years in the form of values based supply chain due diligence laws—mainly, though not entirely, with origins in European states and the EU. The US interdiction of blood diamonds and the use of child labor in mines in certain regions also touches on this aspect of cultural compliance.

Nonetheless, the issue of cultural responsibilities occurs in its most lively and common sense where an enterprise adopts international law or norms—especially in the form of international soft aw (e.g. the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights; the Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination; the UN Sustainability Development Goals and the 2030 Action Plan; and the like). But it may also derive from the application of Treaty law even where the home state has not either acceded to the Treaty or transposed its obligations into national law. It is in this sense that substantial issues of cultural conflict may occur. The issue, though, isn’t whether the enterprise is prioritizing one national culture for another, but the extent to which its compliance obligations make is necessary or plausible for the enterprise to apply cultural expectations built into this international hard and soft law instruments.

Ironically, the issue of corporate cultural responsibilities in its third sense is trans-ideological—that is it is not inherently an issue for liberal democratic states. Chinese Marxist-Leninist principles may appear in the offshore operations of national enterprises in ways that may prioritize home state cultural principles over those of the states in which they operate as effectively as it may occur in the operations of liberal democratic home state enterprises.

In its fourth sense, the term can refer to cultural impacts of economic activity. It is in this sense that local sensitivities sometimes bleeds into political consequences. The issue of cultural impacts is both quite broad and hard to define. All business activity affects its surroundings. It is where that change triggers a response grounded in cultural offense, or fear of cultural interference or change, that the issue becomes sensitive. Cultural impacts can originate in the impacts of producers produced or introduced into a locality. It can also originate in the practices of production followed by an enterprise.

Cultural impact can sometimes be quire conscious and strategic. For example, a foreign corporation seeking to empower women may hire females and pay them well with the expectation that their wages can be used to liberate them from traditional cultural constraints (and the power of their husbands or family groups) to the extent that they acquire more control over their lives. To the extent that this accords with cultural compliance (international efforts at female empowerment), the effect is doubly important for the enterprise.

But sometimes the effect is unconscious. Most famous perhaps is the effect of offering plastic containers on cultures of using local containers made from locally sourced materials. That may have significant effects on labor organization in villages, and to the extent that the plastic containers may leech toxic materials it may also have effects on health. Selling popular music produced elsewhere by foreign artists may significantly affect cultural attitudes and practices, especially in traditional societies. A last involves economic activities on land that is held sacred, the desecration of which can substantially jeopardize the integrity of the community.

Gulan Media: Considering the multicultural and multi-religious nature of the Kurdistan region in Iraq, where peaceful coexistence is prominent, we are interested in understanding the significance of constitutional law of religion. Specifically, we would like to explore how this concept can contribute to fostering unity, cohabitation, and tolerance among diverse religious communities. Furthermore, we are curious about the potential benefits and helpfulness of implementing constitutional law of religion in such a context.

Professor Larry Catá Backer: Thanks for this profound and profoundly interesting question. The issue is certainly one that many groups, including significant, the United Nations and its High Commissioner for Human Rights, have sought to find good solutions. Context matters, of course. Many states are tied to modern versions of classical predispositions to some form of theocratic organization—the alignment of the religious law (broadly understood) of a dominant group as a template against which it is possible to legislate (to the extent it accords with majority theology) other sects, including majority religious sects deemed heretical. Other states are consciously secular—France is an excellent example of a system of religious cohabitation grounded in principles of laïcité, in which religious scruples, practices, and the like, must be aligned to the overarching and superior needs of secular social solidarity; Marxist-Leninist states offer a variation with sub-variations between for example China, Cuba, and Vietnam. . A critical aspect of any peaceful and tolerant resolution of the issues, especially in multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious states or regions, like Kurdistan, may well lie in an effective constitutionalization of a law of religion.

In the casebook that my co-author Frank Ravitch and I wrote about the U.S. system, we note its peculiarities, strengths and challenges. First, the U.S. constitutional system of religion is in some respects intensely contextual in time and place. It reflects an effort at accommodation at the end of a long period of warfare among Christians, and in a context of limited toleration for non-Christian sects. Nonetheless, the construction of the text of that system of toleration allowed for a substantial degree of flexibility that has proven useful as the religious composition of the people of the United States has changed over the centuries. Some of its lessons may be useful for other states as a means of building institutional structures for mutual toleration and respect within a single political community. In most cases, these principles may have to be modified to suit context, expectation, and the sensibilities of the political community seeking to use them to build broadly tolerant and respectful communities of believers aligned in solidarity around a political state.

First, a principle of non-interference is a central element of constitutionalization. What that means is that the state or government at any level may not control, judge, or seek to guide or manage the practices, theology, or internal operations of a religious group. There are limits of course. Those are discovered and dealt with pragmatically. For example public law may continue to apply to much of the operations of a religious group within society—property ownership, business activities, pollution, health and safety rules and the like. But as regulations come closer to religious practices their protection become a more intense matter of scrutiny.

Second, a principle of neutrality characterizes a core principle of analysis in the protection of religious rights. Certainly, at its core, and much more recently, the principle has been applied to prevent any sort of privileging one religion against others. No religion may be treated more favorably or unfavorably than other. This extends to practices that may be offensive to social norms (animal sacrifice, the use of narcotics in rituals); or which may be offensive to other religions (the practice of Satan worship, or forms of paganism, and the like). During some periods of US history the principle of neutrality extends to neutrality between religion and secular interests. That is that the state may not favor religious interest over secular ones. Neutrality has also come to mean that when the state offers a benefit it may not deny that benefit to religious groups solely because they are religious organizations.

Third, a principle a strict protection of belief but not of conduct is necessary. The state cannot be in the business of heresy. Nor can it appear to help groups within religions advance or protect their own sense of belief structures. All religions are free to embrace whatever beliefs are to their satisfaction revealed to them and to adhere to their belief in the power of that revelation and the authenticity of its messengers. However, there are limits to the transposition of belief into action or practice. Not all practice is entitled to the same level of protection, and some practices may be suppressed entirely. For example, a belief in the ritual importance of human sacrifice may be tolerated, but all actions that indicate even the slightest movement toward realizing this belief may be suppressed by all lawful means. At the other extreme, the rituals associated with worship, especially in the forms of the rituals of communal expressions of affirmation of religious belief through prayer and the like, are most strongly protected. In the middle are a broad set of beliefs the expression of which may or may not be subject to control. That control may depend on balancing the right to religious expression with the protection of other constitutional rights. A current highly disputed area concerns the refusal, on religious grounds, to offer commercial services to people. A less controversial example involves the prohibition of plural marriage, even where a religion permits or encourages a belief in plural marriage.

Fourth, a principle of unimpeded conversion between religions or to agnosticism or atheism is absolutely necessary. The protection of a religious community against heresy is protected to the extent that a religious group may police its own internal affairs and expel or discipline members for error or heresy. At the same time, all people are vested with religious rights, not just religious communities. It follows that all people are free to join a religious community (if accepted by them) but more importantly, to leave a religious community and convert to another or become an atheist or agnostic, without the power of a religious community to compel the person to remain or to punish the person for apostasy. The power of a religious community is thus based on its ability to induce solidarity; but they are not permitted to control or punish apostasy.

Fifth, a principle of the supremacy of national interest must be protected. The belief-conduct distinction is grounded on a notion that the national common good must prevail where the interest of the people as a whole is said to outweigh the important value of fostering religious solidarity and protecting religious communities in their practices. While the application of the rule has varied widely over the centuries, the idea is that the state must accommodate religion unless it can demonstrate an important public interest and that there were no alternatives that afforded greater protection to the religious practice that was affected by the governmental action.

Sixth, a principle that religion is personal as well as communal. Traditionally religion was understood as a collective enterprise. Religion was aligned with the institutional structures developed to guide the ‘ummah (Quran 49:10 etc.) or more generally the body of believers (e.g., the Church as the Body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12:12-14)). More recently the constitutional law of religion vests in every individual religious autonomy. In this sense the state does not recognize heresy; it recognizes only individual belief, even if that belief deviates from the orthodox, at least for purposes of protecting the constitutional right of individuals to exercise their faith.

Seventh, a principle of flexible application must prevail. Perhaps this is the most important principle of a constitutionalized law of religion in the US. The constitutional protection is well understood at its core. But it is ambiguous enough to perfect multiple interpretations that accord generally with its principles. That has permitted the courts—sometimes more and sometimes less successfully—to align interpretation of the constitutional law of religion with the times. In the U.S. one can see this in the extraordinary shift in interpretation of the constitutional provision between 1947 ,when interpretations that favored walls of separation between religion and the state, and that interpreted the right of the state to regulate religious practices more broadly, and the current period, when notions of separation have given way to enhanced application of neutrality and the right of state interests to prevail over religious practices has been substantially reduced in scope.

Gulan Media: To what extent would the future trajectory of the country be affected by the non-implementation of the Iraqi constitution, which was rewritten and accepted in 2005, and the absence of federal Iraqi law, considering that the Kurdistan region is an integral part of federal Iraq and there are no other autonomous regions in the country?

Professor Larry Catá Backer: Many thanks for this quite sensitive question. I recall the process of first developing the current constitution for Iraq. I also recall the many sensitivities reflected in an ancient land bringing together many ancient peoples. And I am sensitive to the realities, now thousands of years in the making of a political community that sits either at the center of empire or at the borderlands of other large and imperial political communities.

The question, of course, challenges any simple answer. I can very briefly offer this: There is no magic or imperative for a highly centralized state. Except in matters of collective defense, it is possible, and certainly has been demonstrably possible since the time of the united Greek defense against the Persians under Darius and Xerxes, for a state to be infinitely de-centralized and yet quite vibrantly viable. Likewise a state made up of many peoples may celebrate the diversity of its people and still construct a unified state. At one extreme one has the example of the European Union; at the other the de-centralization of the regions in Spain. Thus there is no magic or rule that mandates that a state be centralized, that central authorities have substantial control over the affairs of its region, or that the many regions of a state conform their governance in all respects. At the same time, it is necessary for a regionally de-centralized state to ensure that its center is well enough resourced and empowered to undertake whatever unifying objectives are set forth for it. National defense is one critical area; infrastructure and connectivity is another; speaking with one voice to foreigners, at least on critical questions of national solidarity is another; basic rights and free movement of its people and their capital and investments among the regions is yet another. Open questions touch on natural resources, family law, development and the like.

With that in mind, it follows that some form of national constitution, and constitutional order is necessary, even vital, for the mutual protection and prosperity of the peoples of the nation. At the same time there is nothing magical, sacred, or compelling about any specific manifestation of a constitutional necessity for the solidification of a decentralized but united Iraq.

Gulan Media: How crucial is the presence of a local constitution for autonomous regions in a federal country, considering that the Kurdistan region has not yet formulated and enacted its own constitution, while the enforcement of the federal constitution remains incomplete?

Professor Larry Catá Backer: Given the answer to the previous question, the answer to this one is a most unambiguous yes. In a de-centralized state, a regional constitution becomes quite important. It is important first to give form to the region as an autonomous unit within a larger state. Second, the constitution serv es as the template for the constitution of lawful authority and for the rules under which that lawful authority may be authoritatively exercised. Third, it provides an authoritative memorialization of the rights of the people of the autonomous region, and of the responsibilities of the state and its organs to ensure that the welfare of the people are understood and responsibility for its realization are specified.

Gulan Media: To what extent will the United Nations address international law violations in critical global issues like climate change, AI and technology risks, and nuclear weapon proliferation? Will the United Nations take action or establish a comprehensive legal framework to tackle these challenges?

Professor Larry Catá Backer: Thank you, a most interesting question. It really suggests two questions. The first is whether the UN will address these issues; the second is whether those activities will at all be useful or relevant. Let’s take them one at a time.

The UN is currently deeply involved in many of the issues identified in the question: climate change, AI and tech risks, and nuclear weapons proliferation. Indeed only several weeks ago the UN Secretary General made a passionate plea for greater UN involvement in issues around AI, big data and digitalized analytics. It is likely that both the UN’s operations in New York and in Geneva will be working diligently on these issues. In both places the consideration will provide an opportunity for states and other actors to work together to identify issues and pathways to movement that accord with the interests, exp4ectsations, and agendas of those with the power and influence to affect these significant issues. Crucial civil society actors will play a role and through the UN’s treaty based mechanisms (its ten treaty bodies) and charter-based mechanisms (including the currently 58 special procedures within the Human Rights Council system), experts, academics, and others may also add their voices. Lastly, with respect to what can euphemistically be labelled “international law violations”—the International Criminal Court as well as the International Court of Justice are already gearing up to add their voices and the weight of their authority; now critically in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian war, but that may serve as a template for other violations.

If it is clear that the UN has the capacity and appetite to confront these issues, then the question remains, what is likely to develop from these considerations. It is possible, though, to offer some suggestions about likely paths.

First, further international law is not likely in the short term. It took nearly a generation to move from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to a fractures set of International Covenants, the universal acceptance of which remains aspirational. The conflicting needs of powerful states, and somewhat powerful blocks of less powerful states, may make any hope of translating desire into consensus, and consensus into an agreed upon legal text.

Second, international norms are a far more likely outcome, though their quality and comprehensiveness will likely vary with the topic. Nuclear proliferation covers very old ground and is the most likely to see something like consensus—though even that may be elusive gen the ambitions of emerging nuclear powers and the likelihood that should they become nuclear states, others, including Iraq may see no choice but to join the nuclear club themselves—or to seek string protection from states already in the nuclear club. Soft law principles, norms, or investigations are also likely in the area of AI and digitalization. There the issue will be one of aligning the aspirations of the three major blocs—US/EU/PRC—a task easier to conceive than to real8ize. In any case AI regulation at a supra national level is coming; its first principles are likely to follow and from within the UN framework. With respect to climate change the template is also well developed at the international level. These may include very general aspirational legal frameworks, and essentially non-binding but discursively powerful. I would expect to see more.

Third, it is likely that the UN Charter-based special procedures (independent human rights experts who report and advise on country situations or thematic issues in all parts of the world)will likely drive some of this movement. They will seek to embed the issues within the scope of their own mandate—either country or thematic mandates. Thus, for example, the UN Working Group for Business and Human Rights might be inclined to consider the human rights effects of AI and climate change in the course of its work. And so on. These actions will have little legal effect but they will cumulatively have a powerful effect on the control and direction of the discourse and narratives around which the issues are considered. It is in this context that states that may not be the most influential in the UN system might leverage their own positions. That has been done before to powerful effect.

Gulan Media: To what extent does the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war pose a threat to international laws and global stability?

Professor Larry Catá Backer: It remains to be seen, of course, but it seems likely that the Russo-Ukrainian war will have a lasting effect. The real question is the nature of that effect. Nonetheless, one can begin to see the glimmerings of trajectories of change.

First, it has recast the nature of Russian involvement around its peripheries and zones of special interest. These include Georgia, Syria, Byelorussia; Moldova, the Baltic region, and to a lesser extent Japan and Korea. It will be difficult to maintain the old narratives about the nature of those engagements against what has emerged as the narrative of the Ukrainian invasion.

Second, it provides a glimpse of the construction of the post-global order. That appears to be being built around concentric circles of dependence around at least two great hubs. For the moment Russia appears to have lost its autonomy within that construction and for all of its power, it appears no longer to be universally viewed as a first tier power. However, it also suggests that in order to check its dependence on its Chinese patron, Russia will seek to build a second order system with itself at the center and looking south toward the Shi’a heartland.

Third, it has exposed some of the great contradictions of the power system (installed for verry good reason after 1945) embodied in the UN Security Council. I might expect substantial resistance but eventual modification of some sort—but one that would preserve the apex power of the two core post-global apex states, with a possible space for an amalgamated European entity.

Fourth, the legalization of the laws of war will continue to be refined and the role of the International Criminal Court may be enhanced. Certainly one of the most interesting aspects of the conduct of this war has been the way that an alliance of public actors and civil society have banded together into networks that have been devoted to a real time collection of evidence to be used in war crimes trials. Once that system is solidified, there will be no turning back from its use.

Fifth, the role of great private actors—corporations as well as elite global civil society collectives—will continue to grow as autonomous international actors. The best example, of course, is the effect of the Starlink system in assuring Ukrainian connectivity at a crucial early stage of the war. There is no going back on this either. A trajectory now several generations old, of delegating crucial functions to private actors, and of solidifying transnational space as a place for autonomous action by private actors, has now effectively transformed private actors.

Sixth, the effect of the Russo-Ukrainian war on global stability has yet to be written. It could go either way. On the one hand, assuming that Ukraine’s allies actually follow through (not a strong suit for liberal democracy acting in the form of a loose coalition of interest advancing partners), the world that emerges from a Russian retreat may well be different—vastly different, but still stable in its own way. The trick here will be to assure Ukrainian victory while preserving the viability of a Russian Federation. And the repercussions will affect all states with substantial unrealized territorial claims. Nonetheless that last caveat also suggests that that one can expect a certain measure of instability in the wake of the Russo-Ukrainian war, however it is resolved. The post 1945 institutions will have been weakened and in the absence of reform will provide no security against public or private misconduct. In the absence of any legal consequences, the state of international law for “big ticket” violations will suffer. Most critically the narrative of international rule of law and of the equality of states—already stretched beyond its reasonable limits—will be exposed as at best weakly aspirational. The choice will be made by a set of the most powerful states, though, at a time when their own internal contradictions have weakened them all, or at least distracted them enough to make it difficult for them to embrace their global responsibilities.

Gulan Media: And lastly, if there is anything else you may want to comment on that we haven’t asked about feel free to tell us .

Professor Larry Catá Backer: Thank you for the opportunity to share some thoughts with you and your audience. We do live in times of great change—the direction of which remains obscured, at least in their detail. It is a time when all political collectives, however big or small, and where ever situated to have in mind the need for building their own protective structures of solidarity. These must have the effect of significantly strengthening internal cohesion. At the same time it must serve as a basis for developing strong ties and peaceful relations among the circles of other collectives with which it is nece4ssary to maintain strong and sometimes intimate relations. I look forward to observing how that will manifest itself in and around Iraq.