The State of the Kurds

June 20, 2015

From Media

It is a time of good news for the Kurds, a people more accustomed to tragedy than to triumph.

Just last week in Turkey, a political party rooted in the struggle for Kurdish rights vaulted over the 10% threshold for parliamentary representation, giving the Kurds their biggest say ever in Turkish politics. Days later, allied Kurdish fighters in Syria seized a crucial border crossing from Islamic State, thus uniting Kurdish areas that now stretch from Iraq halfway to the Mediterranean Sea.

In Iraq, the Kurds repelled an assault by Islamic State last year, and their budding autonomous government in northern Iraq has taken advantage of the collapse of the Iraqi army to seize full control of the disputed northern city of Kirkuk—often dubbed the “Kurdish Jerusalem” because of its historic significance—and the all-important oil fields nearby.

Amid an imploding Middle East ravaged by religious hatreds, the Kurds are providing a rare bright spot—and their success story is finding fresh support and sympathy in the West. By contrast with the rest of the region, all the main Kurdish movements today are broadly pro-Western and secular (though their politicians often don’t practice what they preach, and many Kurds are very traditional).

“We are now living a Kurdish moment in the history of the region,” said Kendal Nezan, director of the Kurdish Institute of Paris, a think tank formed in 1983 to unite Kurdish intellectuals and rally Western support. “The Kurdish project is a project of pluralism, democracy and protection for minority rights—which is something new for the Middle East as we know it.”

The Kurdish awakening has emerged from the upheaval of the 2011 Arab Spring, and it is adding fresh disruption to the region’s old order. “The events in Iraq, in Syria and in Turkey have profoundly altered the place of the Kurds in the Middle East—they provide fresh impetus and momentum toward Kurdish independence in some form,” said Ryan Crocker, who served as U.S. ambassador to Iraq and to Syria and is now dean of the Bush School of Government at Texas A&M University. Such Kurdish independence, he cautioned, “could produce permanent fragmentation of Iraq and Syria—and launch a whole new dimension of instability in the Middle East.”

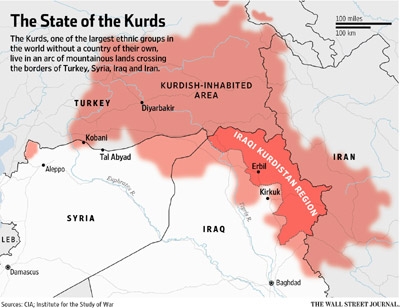

Numbering some 30 million people, the Kurds are one of the world’s largest ethnic groups without a state of their own, scattered since antiquity in the mountainous lands straddling today’s Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq. Their language, Kurdish, is part of the Indo-European family of languages—close to Persian (Farsi) but unrelated to Arabic or Turkish. Unlike Iranians, who are mostly Shiite Muslims, most Kurds are Sunnis.

After World War I, the Kurds sought self-rule at the 1920 peace negotiations between the defeated Ottoman government and the victorious allies. The resulting Treaty of Sèvres called for the establishment within a year of an independent Kurdistan in what is now southeastern Turkey, with the prospect of quick “voluntary adhesion” to the new country by the Kurdish areas of northern Iraq.

But the Sèvres accord was dead on arrival. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, denounced it as treasonous and launched a war that led to the abolition of the Ottoman state. The brief glimmer of hope for Kurdish self-rule was extinguished for generations.

In the following decades, Atatürk’s fiercely nationalist Turkey denied the very existence of the Kurds, banning their language and officially referring to them as “mountain Turks.” By the mid-1980s, a far-left guerrilla movement, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, was fighting a bloody war against the Turkish state (and against fellow Kurds whom it viewed as collaborators). The fighting ended only after the PKK’s leader Abdullah Ocalan, who had been jailed by Turkey since 1999, proclaimed a cease fire in March 2013.

Across the border in Iraq, Kurdish autonomy was sometimes recognized, but Kurdish uprisings were ruthlessly suppressed by successive governments. Repression reached its bloody peak in 1988, when Saddam Hussein’s forces used chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians during the so-called Anfal campaign. As for Syria, though it backed the PKK against Turkey, it stripped many of its own Kurds of Syrian citizenship. And in Iran, both the shah and the Islamic Republic that overthrew his monarchy in 1979 have suppressed Kurdish aspirations.

The quarreling Kurds, with their alphabet soup of rival political groups, have also repeatedly undermined their own cause. In 1982, Saddam Hussein remarked that he didn’t have to worry about the Kurds because they were “hopelessly divided against each other.” Indeed, the two main Kurdish factions in Iraq—the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan—fought a devastating civil war the following decade, though they had reconciled by the time the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, ousting Saddam’s regime and giving the Kurds an unprecedented opportunity.

The new Iraqi constitution adopted after the U.S. invasion enshrined broad powers for an autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government, or KRG, that is home to six million people. Control over their own affairs has allowed the Kurds to achieve what many in the region have called a “Kurdish miracle” in northern Iraq. A boom in investment and construction has produced new highways, hotels and shopping malls that feel worlds away from strife-torn Iraqi cities such as Baghdad and Mosul. “While the rest of Iraq was nose-diving into civil war, everyone was talking about the success story of Kurdistan,” said Cale Salih, an Iraqi Kurdish analyst and a fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

The Kurdistan government in northern Iraq maintains its own armed forces, known as the Peshmerga (literally, “those who confront death”). No Iraqi troops are allowed in the Kurdish region, which controls its own borders, and Westerners can fly into the region’s capital, Erbil, without a visa. Kurdish is used everywhere as the official language, and few young Iraqi Kurds can speak fluent Arabic. A giant green, white and red Kurdish banner flies from Erbil’s ancient hilltop citadel, while Iraqi flags are hard to spot.

In 2011, the Arab Spring opened still other possibilities for the Kurds. The PKK, once an ally of the Assad regime in Damascus (and still classified as a terrorist group by the U.S. and Turkey), had long been present among Kurdish communities in northern Syria. When the revolutionary tide reached Syria, the group’s Syrian affiliate quickly seized control of three Kurdish-majority regions along the Turkish frontier. PKK fighters and weapons streamed there from other parts of Kurdistan.

Last fall, international attention focused on one of these areas, the town of Kobani, when it came under attack by the newly powerful Islamic State. Tens of thousands of Kurdish refugees fled into Turkey, and outgunned Kurdish defenders waged street battles against Islamic State’s onslaught. But Turkey refused to help, arguing that the Kurdish fighters were no better than Islamic State’s militants.

As the city of Kobani seemed poised to fall, the U.S. entered the fray, launching waves of airstrikes that eventually tilted the balance. After fully liberating Kobani in January, Syrian Kurds were able to take the offensive, culminating with the expulsion this week of Islamic State from the strategic border town of Tal Abyad.

Turkey’s authoritarian President Recep Tayyip Erdogan paid a heavy political price for his decisions during the Kobani crisis. Traditionally, his party had won a large proportion of votes among Turkey’s conservative Kurds, many of whom had rewarded Mr. Erdogan for his initiatives to negotiate peace with the PKK and to relax restrictions on Kurdish language and culture—as well as for years of economic growth in long-neglected Kurdish areas of the country. But in elections held on June 7, many Kurds deserted Mr. Erdogan’s party and voted instead for the People’s Democratic Party, or HDP, which was backed by the banned PKK.

“In the past, I voted for Erdogan because he was talking about the peace process, but after Kobani, I realized that he was cheating us,” said Bedri Ateş, a farmer from near Diyarbakir, the largest city in the predominantly Kurdish parts of Turkey.

The HDP campaigned on a broader agenda and won 13% of the national vote, including ballots from non-Kurds who liked the party’s support for the rights of women, gays and religious minorities. But the main message of the HDP’s triumph—which deprived Mr. Erdogan of a parliamentary majority for the first time in 12 years—was that Turkey’s Kurds can no longer be ignored.

“The Kurds’ existence was not recognized; they were hidden behind a veil. But now, after being invisible for a century, they are taking their place on the international stage,” the party’s chairman, Selahattin Demirtas, said in an interview this week. “Today, international powers can no longer resolve any issue in the Middle East without taking into account the interests of the Kurds.”

Recent turbulence in the region has had, for the Kurds, the unexpected benefit of weakening the traditional enemies of Kurdish independence. “In the past, when the Kurds sought self-rule, the Turks, the Persians and the Arabs were all united against it. Today that’s not true anymore—it’s not possible for the Shiite government in Iraq and Shiite Iran to work together against the Kurds with the Sunni Turkey and the Sunni ISIS,” said Tahir Elçi, a prominent Kurdish lawyer and chairman of the bar in Diyarbakir (using another name for Islamic State). “In this environment, the Kurds have become a political and a military power in the Middle East.”

That power was on display in northern Syria this week, as the surprisingly rapid offensive into Tal Abyad led by the PKK’s local affiliate severed the main lines of communication between Turkey and Islamic State’s de facto capital city of Raqqa. Much to Turkey’s fury, the U.S. has provided air support in that offensive, arguing that while the PKK is formally listed as a terrorist organization, that designation does not cover the outlawed group’s Syrian affiliate.

In the battle for Western public opinion, the female military commanders and secularism of the PKK have provided a refreshing contrast to the medieval prohibitions of Islamic State. In Syria, the PKK’s affiliate has even attracted a trickle of American and European volunteer fighters from non-Kurdish backgrounds. Still, factionalism has intruded. In areas of Syria that it controls, the PKK has restricted the activities of rival Kurdish groups, including those allied with the Kurdistan Democratic Party, which dominates the Kurdistan government in northern Iraq.

“The PKK has made important steps to adopt more democratic ways,” said Mr. Elçi, the head of the Diyarbakir bar. “But you cannot find the same climate of political diversity in [Kurdish] Syria as you find in [northern Iraq], and this is because of PKK’s authoritarian and Marxist background. This is a big problem.”

Those tensions aren’t likely to lead to violence this time around, most Kurdish politicians and outside analysts agree. The price of such internecine conflict, after all, would be too high at a time when the Kurds face an existential menace from Islamic State. “The Kurds don’t want this strife anymore. Everyone now knows that such a conflict among Kurds will make everyone a loser and ISIS the only winner,” said Vahap Coşkun, a professor at Dicle University in Diyarbakir who is involved in peace talks between the Turkish government and the PKK.

Still, political divisions do hamper the Kurds’ struggle against Islamic State and their prospects for self-rule. According to Mustafa Sayid Qadir, the minister of Peshmerga affairs in Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government, only a minority of Peshmerga brigades on the front lines are under unified command, and the rest still report directly to one of the two rival political parties.

“The external environment now is more favorable to independence for Kurdistan than before, but our internal affairs are not,” warned Jalal Jawhar, deputy secretary-general of the Movement for Change, the second-largest party in the parliament of Iraqi Kurdistan, which emerged in recent years from a protest movement against the dominance of two older parties. “It is our own fault that we have not prepared ourselves properly for independence. If tomorrow we announced our independence and got dragged into a big war in the region, we would not be ready for it.”

The collapse of the Iraqi army in the face of Islamic State’s advance and continued bickering with the central government in Baghdad over the country’s dwindling oil revenues may end up pushing Iraqi Kurdistan toward such independence anyway. While the Shiite-led government in Baghdad continues to pay the salaries of public employees—roughly half the country’s workforce—in lands controlled by Islamic State, Kurdish public servants and the Peshmerga haven’t been paid for months. Many Kurds also complain that Baghdad is sabotaging their efforts to get better weapons.

“For 80 years, the Arab Sunni people led Iraq—and they destroyed Kurdistan. Now we’ve been for 10 years with the Shiite people [dominant in Baghdad], and they’ve cut the funding and the salaries—how can we count on them as our partner in Iraq?” asked Erbil province’s governor, Nawzad Hadi. “All the facts on the ground encourage the Kurds to be independent.”

Kemal Kirkuki, a former speaker of the Iraqi Kurdistan parliament who now commands 11 Peshmerga brigades on the Kirkuk front lines, agreed: “The Iraqi state has failed, and we need another solution.”

The prospect of an independent Kurdistan in Iraq or northern Syria isn’t something that regional powers such as Turkey and Iran are likely to welcome. The U.S., too, still clings to the idea that a unified Iraq could be brought together again somehow.

American support for the efforts of Iraqi Kurds against Islamic State should not be seen as an endorsement of the Kurds’ wider aspirations, warned Anthony Cordesman, a defense expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington, D.C.

“That’s pretty low-level stuff—that certainly is not a commitment to an independent Kurdistan the moment it becomes irritating to its neighbors,” Mr. Cordesman said. Such a Kurdish state, he added, “has no real great strategic benefits to the U.S. and a lot of potential liabilities.”

Amid the regional war against Islamic State, international assistance to the Kurds represents a tactical choice, not a strategic shift, agreed Gönül Tol, director of the Center for Turkish Studies at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C.: “The Kurds are overconfident. But this doesn’t mean the world is behind them.”

Mr. Demirtas, the leader of the pro-Kurdish HDP party in Turkey, said that he’s aware of this reality—but also urged taking a longer view. “The new reality is that the Kurds are a power that is not temporary anymore. They are a power that is going to stay.”

The Wall Street Journal