Iraq is going to have a new set of problems on its hands whenever ISIS is kicked out of its major cities

May 14, 2015

From Media

It has been almost a year since ISIS exploded across Iraq, taking much of the north and west of the country. This rapid expansion included the seizure of Mosul, the country's second-largest city, along with Saddam Hussein's hometown of Tikrit.

Although a combination of Iraqi Security Forces, Iranian-backed Shiite militias, US airstrikes, and Kurdish forces helped expel ISIS from Tikirt in March, the jihadists are still far from defeat and have even maintained a certain illusion of invincibility. Even with all the forces assailed against them, the militants have continued to steadily make gains on northern Iraq's largest oil refinery at Baiji, only 31 miles away from Tikrit.

Retaking Tikrit required 30,000 soldiers and took several weeks while ISIS might still succeed in taking over Baiji. Both battles only highlight how difficult it's going to be to liberate Mosul, which is Iraq's second-largest city.

But according to a study by Alexandre Mello and Michael Knights of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, forcing ISIS out of Mosul will not be the most difficult part of any operation against the city.

Instead, the hardest part of a Mosul operation will be holding the city and successfully reintegrating it into the country after ISIS is driven back underground.

"What will follow the liberation of cities such as Mosul, Fallujah, and Tall Afar?," Mello and Knights ask. "One option is the Ramadi model— that Islamic State elements will remain in place to mount commuter insurgencies in areas where population centers and economic hubs can be attacked from rural redoubts."

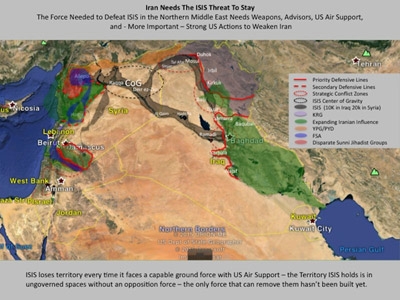

Unless the Iraqi government and its various allies can successfully hold and garrison Mosul while also improving security in the surrounding towns and wilderness, the city will still be in constant risk of falling to the jihadists. Just as in the case of the Baiji oil refinery, ISIS would be able to regroup in ungoverned areas and launch grinding counter-attacks.

"A key lesson of the last six months is that retaking town centers is not a real measure of success," write Mello and Knights. "[S]stabilizing the whole defensive zone, including the rural belts, is the real victory."

"There is nothing mystical about the Islamic State as a defensive force: it has succeeded almost entirely due to the absence of effective opposition, not because of its inherent strength," they write.

This absence of an effective ground-level opposition against ISIS is a result of the priorities of the conflict's various players.

The Iraqi government, Baghdad-allied Iranian-backed Shi'ite militias, and the Kurds don't believe they have much of an incentive to push the front lines of the conflict beyond their current borders. Currently, the war against ISIS has divided Iraq into three zones of control — the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government, the largely Shiite zones that the central government controls, and the ISIS-dominated Sunni north and west.

Any push by the Kurds or the Baghdad government into largely Sunni ISIS-controlled areas will encounter serious problems clearing the militants, earning the trust of the Sunni population, and bringing some semblance of state control back to the newly liberated territory. Without local support, these goals become nearly impossible.

This process will be especially difficult, Mello and Knights note, because ISIS has "destroyed hundreds of police stations, administrative offices, bridges, and official dwellings."

"This is part of a deliberate counter-stabilization effort that may hint at a slow-burn strategy to wear down the Iraqi nation with repeated sorties from insurgent-controlled redoubts in Iraq and Syria," they write. "The Islamic State has failed to hold terrain, but they may prove adept at preventing post-conflict resettlement and stabilization of affected areas."

Unless the Iraqi government can somehow find a way to integrate the Sunnis back into the state and rebuild the institutions and infrastructure that ISIS has destroyed, ISIS will not be fully dislodged from Iraq. And the group is thoroughly entrenched in Mosul, a place that they could contest as an insurgent group even after losing control of the city.

The Business Insider