Iraq: Time for a Three State Solution?

Iraq at the moment is a complex and fluid mix, with the conflict making it particularly hard to judge exactly how the country will end up. Even so, it seems increasingly clear that the most likely outcome is going to be some kind of multi-state solution. What will this look like? How will it function? What is it likely to do to the politics and economics of the wider region?

A three state solution has long been put forward as a possible approach to dealing with the difficulties in Iraq, finding favour at least a decade ago as a possible way of avoiding the conflicts that might result if the international community tried to force Iraq to remain as one state following the fall of Saddam. That these conflicts came to pass does not prove that the three state solution would be successful, but it does suggest that the one state approach has not been.

The biggest problem with Iraq is that it has always been an artificial construct, cobbled together by outside forces as a kind of balance for other regional powers such as Iran. It started life as a way for Britain to gain access to oil resources, and there is an argument that its existence is still doing the same job for other portions of the international community. It has tried foreign rule, monarchy, dictatorship, and most recently a kind of embattled democracy backed by force in an attempt to keep it together, but can that really be achieved in the long term, and would other approaches produce more desirable results?

Typically, the answer to this has been that a united Iraq provides a bulwark against instability and chaos. Yet this has demonstrably not been the case in the last few years. The wars for control of Iraq have not been avoided because it is one nation. Indeed, it is truly one nation only in name. Kurdistan is already independent of Baghdad in every sense that matters. There is a clear de facto division between the Shiite and Sunni areas of central and southern Iraq to add to this.

What will Iraq look like in five years’ time? In ten or twenty? It seems clear that it will not have the borders or size that it had in 1990. It is likely that there will be at least three states. It is possible, albeit unlikely, that there might be more, depending on the internal divisions that come into being within each area. It is possible, albeit unlikely, that there could just be two states, with some form of “Iraq” and some form of “Kurdistan”.

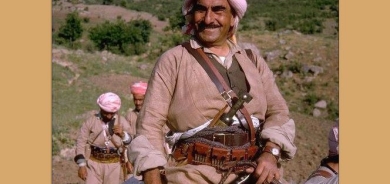

It seems almost certain that the Kurdish areas of Iraq will break away at some point. Exactly what shape they will take is perhaps less certain. Currently, the most likely shape for any independent Kurdistan is that which the Autonomous Region already has, which for the international community may be an argument in favour of supporting independence sooner rather than later. If the situation in Syria drags out much longer, however, there is every chance that a negotiated settlement to it may include Kurdish areas joining up with the KRG controlled Iraqi Kurdistan, or that already unstable areas in surrounding countries might attempt to break away.

This might result in a larger version of Kurdistan than is currently the case, which ironically, might produce exactly the kind of balancing force that elements of the international community are trying to produce by forcing Iraq to stay together. The only situation that might produce such a large version of Kurdistan in the next few years, however, seems to be one where the conflicts in the surrounding regions drag on so long that Kurdistan’s neighbours want no more wars. Otherwise, it seems likely that Turkey and Iran in particular would oppose a new country on that scale.

A smaller Kurdistan, set above an equally small Iraq, seems like a much more likely outcome. The political implications of this for the region are likely to involve the normalisation of the current two way division of wider regional power between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Yet Kurdistan in particular probably would still have a degree of political and economic importance.

This would be because it would represent one of the more stable and friendly areas within the Middle East, open to outside investment, and more moderate than many of its neighbours. It would be a good point of contact for those wishing to build friendly relations in the region, and the kind of political hub that might prove valuable in allowing those from all sides to talk to one another and prevent further conflicts.

Economically, the fortunes of many of the countries in the region are likely to remain based on oil and other natural resources for the foreseeable future, regardless of the size and shape that those countries take. One of the most important points of contention between Kurdistan and Iraq is likely to remain the exact disposition of these resources, and the rate of their exploitation.

As the global economy moves on, however, there is likely to also be room for other avenues in the newly settled states, particularly in higher technology areas. Kurdistan, in particular, may find itself well placed to follow the economic models exploited by other small but economically agile states, serving as both a stopping off point and a way of connecting with the wider region.

Yet this is more of a long term issue, and in the immediate term, Kurdistan’s economic difficulties may appear to be a barrier to the kind of independence that otherwise seems almost inevitable. The collapse of oil prices, coupled with a lack of payments from Baghdad, have created difficulties, and may make it appear as though those difficulties would only increase without any connection to the rest of Iraq to fall back on.

Yet there are also reasons to feel hopeful about the economic prospects for both Kurdistan and the rest of Iraq with a three state solution, simply because of the stability it would produce. It would place Kurdistan, in particular, in a better position to raise its own taxes, as well as seeking revenue from other sources. But it might also mean that Baghdad would be able to restructure the economy around it, without the distraction of believing that Kurdistan’s oil revenue might come back into play at some point.

The broader implications of a three state solution are potentially wide ranging, but also potentially beneficial. By providing a settlement to one of the key conflicts of the region, it has the potential to stabilise other conflicts, including that in Syria. By providing a recognised Kurdish state, it has the potential to prompt a final settlement of Kurdish questions elsewhere, as well as taking some of the sting out of separatist movements.

Certainly, the three state option appears to be a better one than the current attempts to force Iraq to remain as a single entity. That seems only to be prolonging the war in the country, stoking divisions, and damaging the chances of a successful peace, all for the sake of maintaining a largely artificial construct that was only brought into being to solve the problems of an entirely different war.