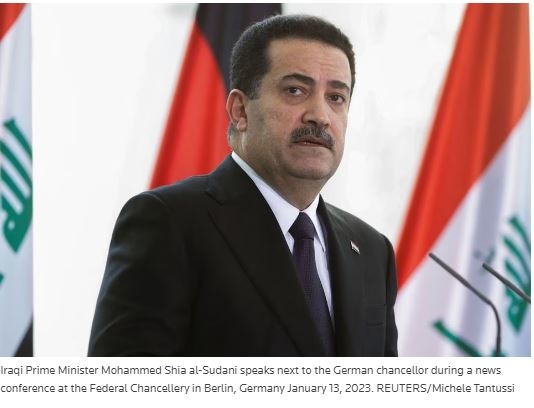

Iraqi PM supports indefinite U.S. troop presence, Wall Street Journal reports

Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed al-Sudani defended the presence of U.S. troops in his country and set no timetable for their withdrawal, signaling a less confrontational posture toward Washington early in his term than his Iran-backed political allies have taken.

“We think that we need the foreign forces,” Mr. Sudani said in his first U.S. interview since taking office in October, referring to the American and North Atlantic Treaty Organization troop contingents that train and assist Iraqi units in countering Islamic State but largely stay out of combat. “Elimination of ISIS needs some more time,” he added.

Until now, Mr. Sudani has been publicly silent about his views on keeping U.S. forces in Iraq, saying only that he would consult Iraqi commanders. Some pro-Iranian militia leaders and Mr. Sudani’s supporters in Parliament are pressing him to reconsider the U.S. presence.

That has left Biden administration officials unsure about the future of around 2,000 American troops in Iraq and a separate multinational training force under NATO command.

Mr. Sudani, who had little international experience and is mostly unknown in the West, is trying to broaden his outreach to the Biden administration and other Western governments in hopes of attracting investment and aid, as well as to counter criticism that his government is too closely aligned with Iran.

For Iraq, the second-largest crude-oil producer in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries after Saudi Arabia, such ambitions face enormous obstacles, including an economy and government plagued by corruption and well-armed militias, a continuing low-level security threat from Islamic State, and divisions among its Shia, Sunni and Kurd factions.

Twenty years after the U.S. invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein, Washington and Baghdad have a wary but still intertwined relationship. Since November, Iraq’s dinar has dropped sharply against the dollar in unofficial currency markets in Iraq’s dollar-dependent economy, raising prices of food and other goods for ordinary Iraqis whose support Mr. Sudani has been courting.

But it is Baghdad’s relationship with Iran that is a particular barrier to Mr. Sudani’s goal of forging closer relations with Washington, analysts say.

“He’s facing an uphill battle from the start because of this American-led unwillingness to view Iraqi politics as anything but a reflection of Iran and as black and white,” said Marsin Alshamary, a research fellow in Iraqi politics at Harvard University’s Kennedy School.

Iraq would like similar relations with Washington to what Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf oil-and-gas producers enjoy, Mr. Sudani said. Those countries have longstanding military and economic ties with the U.S. but have also sought to carve out more-independent positions in recent years, including with Moscow and Tehran.

“We strive for that,” he said of the Gulf countries’ approach. “I don’t see this as an impossible matter, to see Iraq have a good relationship with Iran and the U.S.” He added that President Biden “is different from other presidents in that he knows the situation in Iraq completely.”

In a statement, the State Department said the U.S. wants to see “a strong, stable, and sovereign Iraqi state.”

“Iraq is a vital partner on many issues, and we are eager to deepen our cooperation” on climate change, water security and energy modernization, among other issues, the State Department said.

The 52-year-old former labor minister was chosen as prime minister by Iraq’s Parliament in October, breaking a yearlong impasse with Moqtada al-Sadr, a Shia cleric whose followers delayed the formation of the government for months with violent protests and a nightlong gunbattle last August outside the Parliament building.

Mr. Sudani has promised in his first three months in office to provide jobs and rein in corruption, including among high-level officials involved in moving cash out of the country. Just weeks into his term, Mr. Sudani was faced with a major scandal involving the looting of $2.5 billion in tax revenue from Iraq’s state-owned Rafidain Bank, allegedly by bankers and advisers to former Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi‘s government.

A businessman arrested by authorities confessed involvement and was released on bail, Iraqi officials said. A former adviser to Mr. Kadhimi was also arrested and released on bail, officials said. Dates for their trials haven’t been announced.

Flanked by shoulder-high stacks of bills, Mr. Sudani announced at a news conference last month that more than 300 billion Iraqi dinars, or about $250 million, had been recovered and that those responsible would be prosecuted. “Our investigation will go after any official involved in this matter,” Mr. Sudani said in the interview.

Mr. Sudani, whose father was a sheikh in Iraq’s Sudani tribe who was executed during the Saddam Hussein regime, remained in Iraq during Saddam’s rule, unlike many other Shiite politicians and activists who sought exile in Iran, according to Mr. Sudani’s aides.

But his room to maneuver is limited by Mr. Sadr, who can mobilize thousands of protesters and armed militia members against the government. At the same time, Mr. Sudani has to retain support of the so-called Coordination Framework, a group of mostly Shiite parties and factions that backed him for prime minister. It controls the most seats in Parliament and several key ministries in his cabinet.

One of his main backers remains former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, whose ties to Tehran when he was in office strengthened the militias and intensified sectarian violence. In November, Mr. Sudani visited Tehran, where he called the two countries’ security “indivisible” in a news conference with President Ebrahim Raisi.

Mr. Sudani said in the Journal interview in Baghdad’s presidential palace that he was planning to send a high-level delegation to Washington for talks with U.S. officials next month, a move that aides said they hoped would pave the way for Mr. Sudani to meet Mr. Biden. Last Friday, Mr. Sudani held talks with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Berlin and will travel to France later in the month, aides said.

The State Department said it had no comment on “potential upcoming meetings” with Mr. Sudani and other Iraqi officials.

Mr. Sudani, who met last month in Baghdad with the top U.S. commander in the Middle East, Gen. Michael “Erik” Kurilla, said another reason to keep foreign forces in Iraq is that they provide a logistics hub for resupplying American forces battling the remnants of Islamic State in neighboring Syria, a mission that he acknowledged helps prevent the resurgence of the group in both countries. Around 900 U.S. troops are based in Syria.

The Pentagon has stepped up raids against Islamic State in Syria, with at least 10 operations last month. In Iraq, there were four major attacks believed to have been carried out by the group in December, leaving at least 14 Iraqi soldiers and police officers and 11 civilians dead.

“Inside Iraq we do not need combat forces,” Mr. Sudani said, referring to the U.S. role in assisting with training of Iraqi troops and intelligence in going after Islamic State. “If there is a threat for Iraq, it is the penetration of the [Islamic State] cells through Syria.”

By David S. Cloud and Michael Amon

WSJ