Kurds push to cash in gas reserves

The executives christened the pipeline Nabucco after the Verdi opera they would attend together in Vienna.

But Nabucco, which has yet to lay a centimetre of pipe in the ground, has remained too long in the realm of fiction, says the oil minister of Iraqi Kurdistan, which was to feed gas into the pipeline alongside other regions of Iraq.

"If a pipeline capability does not materialise in time … then we will go for the LNG plant in Ceyhan, [Turkey]," said Ashti Hawrami, threatening to send the gas to international markets by sea rather than waiting to pipe it to Europe over land via Nabucco. "We are in a hurry. We have the gas, we need to monetise the value of this gas, and we cannot wait for investors to come up with a plan."

Although the pipeline plan has received the backing of the EU and a slate of major companies from the countries along its proposed 3,900km path, it has faced delays in the start of construction and ballooning costs from its original budget estimate of €7.9 billion (Dh39.86bn).

Backers of the project, including Austria's OMV and Germany's RWE, say the delays arise from the reluctance of governments in Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan to commit to providing gas for the pipeline.

Supplies from these Central Asian countries are vital to justifying the final cost of the project, which BP - not a Nabucco backer - has estimated to be €14bn because of the high cost of steel.

OMV, which is quarter-owned by Abu Dhabi, says Nabucco might start bringing gas to Europe only in 2018, a year later than planned.

Meanwhile, competitors to Nabucco are gaining traction. They include a Russian pipeline called South Stream that is meant to deliver 63 billion cubic metres of gas a year to Europe - versus Nabucco's proposed capacity of 31 billion cu metres. In March, Wintershall, a German energy company, agreed to back South Stream.

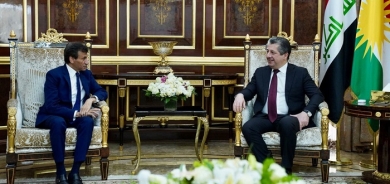

This week in Erbil, Mr Hawrami, the oil minister, made clear his impatience with the delays.

"We will be anxiously awaiting for Nabucco and other project developments in Turkey," he told an audience of energy industry executives from companies including OMV.

Mr Hawrami's sense of urgency represents two aspects of the Kurdish region's approach to its oil industry, which is less than a decade old - speed and pragmatism.

Iraqi Kurdistan has been swift to welcome foreign partners, signing its first oil contract with the Turkish explorer Genel Enerji in 2002, one year before Saddam Hussein was pushed from power.

In the years since, the authorities of this relatively undeveloped region in northern Iraq - said to contain as much as 45 billion barrels of oil - have signed more than 40 production-sharing contracts with other companies, over Baghdad's objections that such agreements violate the Iraqi constitution.

Mr Hawrami, a Baghdad-trained engineer, defends Kurdistan's strategy as a matter of economic necessity and geopolitical safety.

"Waiting for Baghdad to adopt a centralised oil and gas law was not an option for Kurdistan," he said. "We would have remained in the dark with two hours of electricity. We would have been without fuel for cars and factories. We would be still using not suitable drinking water and so on. This would have much bigger ramifications than things not being available for our people. All of that would have meant undermining the region's stability completely."

For now, Kurdistan's extra gas, he said, is going to waste lighting up the sky as it is burnt in the course of oil production.