‘Mediterranea’ brings plight of African migrants to big screen

Few topics could have more international relevance and urgency than the ongoing tragedy of "boat people" crossing the Mediterranean, the subject of Italian-American director Jonas Carpignano’s first feature film, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) says more than 2,600 people have died attempting the hazardous crossing this year – and thousands more have moved on to a precarious existence in Italy and other European countries.

In “Mediterranea”, which screened in the Critics’ Week sidebar on May 19, Carpignano goes beyond the gruesome headlines to focus on the little-known hardships of migrants who set foot on Italian soil, patiently setting the stage for a dramatic reconstruction of the riots that rocked the southern town of Rosarno in 2010. The script is inspired by real events, interviews and the director’s own journey through North Africa – interrupted only when Algerian authorities warned him about the presence of al Qaeda cells in the area.

The film’s beautifully shot opening scenes give a cursory but vivid portrayal of the migrants’ gruelling journey to the sea. Clinging to overloaded trucks or walking through desert terrain, they are easy prey to bandits and exploitative traffickers. Upon reaching the Libyan coast, the migrants find out they have to pilot the rickety vessel themselves because the smugglers won’t do it. Amid the gloom, there is a moment of levity when one man argues that the film’s protagonist Ayiva (Koudous Seihon), who hails from Burkina Faso, cannot pilot the boat because he’s from a landlocked nation and has probably never seen the sea. The Mediterranean’s treacherous waters soon cause the vessel to capsize. Some survive by holding on to a floating structure until they are rescued by the Italian coastguard. A chilling underwater shot reveals the floating bodies of those who didn’t make it.

‘Mamma Africa’

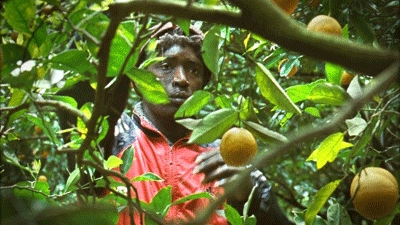

The film follows Ayiva and his friend Abas (Alassane Sy) to Rosarno, in Italy’s southern Calabria region. The two of them have been given a three-month permit to stay in the country, but need to land a job contract to apply for long-tem residency – a near-impossible mission. Calabria turns out to be cold (we’re in the middle of the orange-picking winter season), desolate and with few job prospects. The migrants live in filthy shacks and squats, vulnerable to eviction by the police. They are exploited in orange groves and paid a pittance. The gap between their expectations of Europe and the reality they encounter is glaring. Ayiva promptly tells his sister and daughter, who stayed behind, not to attempt the crossing. The disillusionment is palpable, but so is his profound joy when he sends his first 50 euros and a gift for his daughter back home. While Ayiva is aching to go back, he knows this is not an option.

“Mediterranea” draws an equally insightful portrait of southern Italy, a traditional, economically backward land with a long history of emigration that is ill-equipped for the challenges of immigration. It is a place of contrasts, where the locals’ conflicting instincts of generosity and narrow-mindedness leave the migrants disoriented and insecure. The colourful cast of characters includes an improbable child hoodlum (played by the superb Pio Amato) who trades in stolen goods, and a patronising Good Samaritan who cooks lasagne for the migrants and calls herself “Mamma Africa”. Carpignano is now working on a sequel centred on migrants’ interactions with the fearsome Calabrian mafia. If it’s anything as shrewd as his first feature, it should cast light on another little known facet of the Mediterranean’s great migrant tragedy.

A first version of this article was published in May during the Cannes Film Festival. 'Mediterranea' is set for release in the UK on October 16 (London Film Festival). The US release date is yet to be announced.

FRANCE24