Yemen 2024: Interests, Ethics, and Ideology in a Fractured Tribal Society

Roby C. Barrett

Middle East Institute

With the permission of both the author and the Northern Plains Ethical Journal, Gulan Magazine is republishing this paper.

Zaydi Yemen, Western interests, and the protection of global trade pose a complicated set of riddles for US policy makers. A clan-dominated, sectarian tribal faction in upland Yemen, the al-Houthi family, is determined to disrupt global trade and regional stability while largely ignoring its own population, which is teetering on the brink of a humanitarian disaster. The juxtaposed issues of strategic interests and concerns about the humanitarian disaster have resulted in Western policies that have been confused, inconsistent, at times misguided, and almost always ineffective. Pseudo-ethical considerations, i.e., handwringing over narrow, unsolvable humanitarian issues in southwest Arabia, have undermined pragmatic interest-based policies while at the same time offering no workable alternatives. The naïve notion that the West and its regional allies are more responsible for the situation in Zaydi Yemen than the unstable clan and tribal socio-political structure coupled to the Iranian backed al-Houthi family is nonsense. This inherently paternalistic argument is merely an attempt to shift agency for problems and solutions from the self-absorbed Houthi family and its supporters to the US and its allies. While the US may share some responsibility for short-sighted, ill-informed policies that have aggravated the situation, the principal culpability lies with exploitation of a fractured tribal society by the al-Houthi clan, which is currently beholden to Iran for support. The situation is a self-inflicted Yemeni crisis that has brought the worst of all worlds to upland Yemen and now, due to attacks on shipping in the Red Sea, has created a problem for global trade.

A brief discussion of what is termed here as “pseudo-ethical” policy making and execution is in order. “Pseudo-ethical” refers to the narrow focus on the arguably al-Houthi inflicted and perpetuated humanitarian crisis in upland Yemen as opposed to evaluating the Yemen situation in terms of the pragmatic ethical responsibility to protect global economic stability from trade and supply- chain interruptions as well as the responsibility to restore predominately Sunni regions to Sunni control. In the West, the arguments that have hindered pragmatic, measured, decisive action in situations like Yemen are a byproduct of paternalism of the colonial experience. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the general Western acceptance of colonialism, whether direct or indirect, was justified through various mutations of concepts like Social Darwinism or the ideas expressed in Frederick Lugard’s Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa.1 These theories served to rationalize the ethical conundrum posed by the European-dominated social and economic globalization that emerged in the 18th century – the period corresponding to the Second British Empire and subsequent post-1945 Pax Americana. Prior to the late 18th century and emergence of the ideals of the Enlightenment and of the American and French Revolutions – liberte, egalite, fraternite – imperial powers felt little compunction to explain or justify their actions. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the often-glaring inconsistencies between “western ideals” and colonial realities brought pressure to justify a system in which “westernized” societies enjoyed political and economic advantages that far exceeded those of the rest of the world. As a corollary, the post-1945 era witnessed the rise of the idea that economic development could bring the developing world to a “take-off” point where rising prosperity would bring with it liberal democratic institutions and stability.2 The fulfillment of these ideals and policies were to an extent seen as the West’s obligation to rectify the situation created by colonial rule.

Obligation or not, by the 1970s, this optimism about progress in the developing world had begun to fade. Most of these ideas were on life support, if not dead, but they were not buried. As a result, the West, and particularly the United States, found itself hopelessly tilting at various windmills seeking to bring Western-style governance and civil society to regions or polities where there was no realistic chance of succeeding. In the post-1945 era, a series of international, state-sponsored, and non-governmental organizations emerged as an industry that focused on stop-gap measures to deal with global humanitarian crises – stop-gap because no real solutions existed. Their focus was not the broader context but rather to elevate the visibility of and to assign responsibility for specific crises. These efforts have been viewed as an ethical imperative – the responsibility of ‘more advanced’ societies. At the same time, Western policy makers, stumbling over the attempted implementation of Western ideals and forms that were fundamentally foreign to the reality on the ground, were unable to effectively pursue hard national or international interests. Pragmatic policies and interests were often undermined by narrow pseudo-ethical considerations and western policies and expectations that were totally impractical for the situation at hand.

Not surprisingly, various policy disasters ensued. That list is long; therefore, only three examples are cited here. For example, in Iraq, Saddam Hussein was a tyrant and his invasion of Kuwait in 1990–1991 had to be reversed, but in 2003, were US interests served by invading Iraq, instituting “democracy”, and placing sectarian Shi’a groups beholden to Iran in charge? In Afghanistan, the Taliban regime offered safe-haven to Al Qaeda which brought the 2001-2002 intervention; but subsequent to that, was it realistic to believe that the US and its NATO partners were going to create a stable pluralistic society governed by civil discourse where rights of women and minorities were respected and patronage- based corruption was eliminated – seriously, in Afghanistan? In Yemen, the attempt to curb al-Houthi expansion into the Sunni Tihama and take control of the port of Hodeidah was off limits in part because it would exacerbate the humanitarian crisis for which the policies of the Houthi clan were in large part responsible. The port and coast remained in Houthi hands; some aid arrived, along with significant quantities of long-range Iranian supplied weapons. Now the US and the West are confronted by another policy challenge in Yemen, and the focus needs to be on its interests and not pseudo-ethical considerations related to unsolvable political, economic, and socio-cultural problems.

The “Yemen Crisis” of the 21st century is just another chapter in what for the last 500 years has been the unstable suppurating aggravation of southwestern Arabia. Yemen. In particular, upland Zaydi Yemen has been a global poster child for feudalism, tribalism, and underdevelopment that perpetually teeters on the precipice of becoming a full-blown humanitarian disaster. Since the decline of the coffee trade in the late 18th century, Yemen has virtually no value to anyone except as geo-political leverage in broader regional and international struggles. That is exactly where we find ourselves today – “nothing new under the sun.” The only commodity of value that Yemen can barter is instability. Arabia Felix is neither “happy” nor “fortunate.” The same can be said of those that must deal with it. Setting aside all the handwringing about humanitarian disasters – self-inflicted or not – and the pie-in-the-sky talk of “development,” dealing with Yemen requires coming to grips with three absolute givens. First and foremost, the term “Yemen”

is a geographical term that has never and does not now refer to a state. Second, the political, economic, and socio-cultural problems of Yemen cannot be solved – no amount of aid or effort can change that reality. The countless Yemeni migrations – whether to Oman in the 1st century CE, to 8th century Umayyad Syria and Al Andalus, to 19th century Vietnam or 20th century Detroit – not to mention the Indian Ocean littorals – provide conclusive evidence that the grass has always been greener elsewhere. Third, and perhaps most important, is the recognition that Yemen’s only consistent value in the modern era has been as an aggravation.

Yemen is a beautiful, fascinating place of no intrinsic value – that is, other than its strategic geographic location. Whether as Red Sea and Indian Ocean pirates in the 17th and 18th centuries, a potential flashpoint between the British and Ottoman Empires in the 19th century, and a Cold War pawn in the 20th century, Yemen’s only real worth is in its negative impact on the interests of empires and its neighbors.3 In the 21st century, that has not changed – the Houthi clan barters Zaydi Yemen’s ability to threaten the oil production in the Gulf, shipping in the Red Sea, and pinpricks aimed at Israel for Iranian aid, political distraction at home, and perhaps international political leverage. Sunni Yemen offers its potential to block Houthi ambitions and Iranian influence in return for financial aid and military support. In both cases, Sunni and Zaydi, the Yemen issue is more about the family, clan, and tribal influence than it is about broader sectarian convictions or political identity. Herein lies the point of this essay – the fractious, chaotic nature of Yemeni society and politics – the very thing that makes Yemen so difficult to deal with – ironically provides the only pathway to potentially mitigate the more unacceptable aspects of Yemen or southwest Arabia’s impact on regional and global interests. In short, the game in Yemen must be played by Yemeni rules.

In 2016, this author, responding to a request from Special Operations Central Command (SOCCENT), provided a pro bono white paper for those working on the “Yemen problem.” The introduction read as follows: “Wars in Yemen cannot be ‘won’; nevertheless, strategic goals in Yemen can rarely be achieved, no matter how tenuous, without the political leverage created by military conflict. In the case of Yemen, an adapted Clausewitzian view absolutely applies, “The political objective is the goal, war is a means of reaching it, and must never be considered in isolation.” In simplest terms, the West and its Arab Gulf allies find themselves facing one of two prospects for the future: the prospect of a “Hezbollah-like” Zaydi Shi’a regime in Yemen supported by Iran or a partitioned Yemen based on its dual Zaydi and Shafi’i Sunni heritage that reflects the historical political, economic, and cultural reality of southwestern Arabia.”

Now, seven years later, the accuracy of the statement has been largely borne out. That said, it could have been much worse. At the time, a surprise but strained alliance between former President Ali Abdullah Saleh (1979–2012) and the Houthi clan from Sa’ada, whose security forces had killed Hussein al-Houthi in 2004, threatened to reassert control over most of Yemen. In a subsequent predictable falling out, Hussein’s brother, Abd-al-Malik al-Houthi, the new Houthi leader, assassinated Saleh, but not before a US-backed, Saudi-Emirati intervention thwarted a northern takeover of the south, leaving the political situation in Yemen unstable and unresolved with a Zaydi rump state in the north and fragmented Sunni groups in the south, east, and coastal areas. Of course, the idea that a politically stable entity, even a decentralized one, would emerge was an absurdity. Nevertheless, fractured chaos has been preferable to a consolidated Zaydi regime in control of Yemen’s limited oil resources and dominating the Sunni regions.

That Yemen is once again on the policy priority list of unignorable problems should surprise no one, but dealing with this current challenge requires something new – a broader understanding of the Yemen context and an honest appraisal of how this situation arose in the first place. While Ansar Allah and its Houthi leadership’s sudden affinity for Palestinians is no doubt encouraged by Iranian financial and military aid, the Houthis attempting to take an active role in the Gaza conflict has far more to do with issues closer to home than any affinity for the suffering of Palestinians. In part, it is a quid pro quo for Iranian support and provides a distraction from the acute social and economic distress that has consumed upland Yemen since the Houthi takeover. Houthi controlled areas of Yemen constitute an international basket case in large part due to the ineptitude of

the Houthi clan in dealing with its neighbors. The Houthi clan requires outside backing not only against its Yemeni Sunni rivals, Riyadh, and Abu Dhabi, but also against clan and tribal rivals within the Zaydi community itself where literal and metaphorical backstabbing is a way of life. The Zaydi tribes of central and south- central Yemen tend to view the Sa’ada Zaydis as primitive mountain “jabilis.” Despite having embraced Zaydi revivalism and a neo-Zaydi ideology, Abdul Malik al-Houthi’s first concern is not some imagined theocratic ideological bond between Zaydi Fiver-Shi’sm and the Khomeinist distortion of Jafari Twelver Shi’sm, but rather the certain knowledge that his leadership and the preeminent position of his clan within the Ansar Allah movement is perpetually under threat. For the Houthi clan, just as it was for any imam or Ali Abdullah Saleh, the immediate challenge is survival. Given the reality of Yemen’s instability, it would be surprising if the Houthi family’s actual hold on power is not considerably more tenuous than outward appearances indicate. In the West, policymakers would do well to accept this as a given and see what advantage might be gained from it.

In the West, the failure to pragmatically exploit Yemen’s inherent instability to the detriment of the Houthi clan flows from a lack of tenacity and the propensity for policymakers to delude themselves with the idea that some relatively stable political arrangement might emerge. The lesson that endemic instability and conflict is the Yemen norm seems to require periodic relearning. Yemen is a geographical term applied to a region in which factionalism at the family, clan, and tribal ties dictate political, economic, and sectarian relationships – not the reverse. The geographic region currently designated as Yemen on a map is not now, has never been, and will never be a state. It is what Tahseen Bashir, a noted Egyptian diplomat, described as “tribes with flags.”4 As Robert Burrowes stated, “North Yemen [roughly Houthi dominated Yemen] and Afghanistan [are] more like the other than like any other country in the world.”5 Dealing with this situation requires a fundamentally different kind of outlook and approach – in short, Western norms of civil society or political cohesion are largely missing from the equation.

The West and Yemen: The Idea of a Nation-State

Assessing policy options requires coming to terms with the fact that central authority is a mirage. Politics and the society are fractured at every level and taking advantage of this is the only path to gaining limited tactical influence in any given situation. The game must be played by Yemeni rules – ruthless pursuit of self- interest, paranoia, and fear – not Western notions of political discourse. While applicable to Yemen as a whole, this reality is even more intensely pronounced in Zaydi Yemen. For example, the Sunni Rasulid state (1229–1494) exercised more or less stable political authority over much of coastal Yemen. That was due in no small part to the exclusion of Zaydi tribal Yemen from the political process. Rasulid prosperity and stability contrasted sharply with conditions in the upland Zaydi Imamate. Each succession there involved ten or more candidates from different clans and tribes claiming the right to rule. The Zaydi north remained immersed in feudalism, tribalism, clan rivalries, and personalized rule.6 Unfortunately, the problems of the Zaydi north and its inward looking ‘jabili’ culture have progressively become the norm for all of Yemen.

Ironically, the problems of post-1990 Yemen to a significant degree flowed from Western wishful thinking that saw the potential for Yemen to emerge as a nation-state with the Saleh regime as a segue to a stable, more democratic society based on rule of law. This vision of Yemen promoted the idea of organized political participation and became a vehicle for intensified ideological and sectarian identification through political parties. The upshot was that traditional groups within Yemen, some allied with the Saleh regime and some not, developed a growing political self-awareness. This further

exacerbated Yemen divisions and brought exactly the opposite result that the West had intended. The Zaydi revivalist movement, Ansar Allah (the so-called Houthis) displaced traditional Zaydi leadership in the north emerged as a direct result of this politicization. Almost simultaneously in 1990, Al-Islah, the political party closely associated with Sheikh Abdullah ibn Hussain al-Ahmar’s clan and the Hashid tribal confederation became a new source of Sunni political identity. This was particularly destabilizing because prior to 1990s, the Hashid had contained both Sunni and Zaydi tribal elements because Zaydi Islam and Sunni Islam were viewed as almost one in the same. In Wahhabi Saudi Arabia, Zaydi Imams from the Sa’ada region were invited to lead the prayers at the Grand Mosque in Mecca. The emergence of Ansar Allah and al-Islah introduced pronounced sectarian identity into the mix, fracturing the Hashid Confederation, and undermining one of the principal props of the Saleh regime. Generational issues and personal rivalries played a role as well in undermining the Saleh-al- Ahmar alliance, but the emergence of political parties with sectarian identities split the Hashid.

In the east, politicization increased the sectarian identification among the Bakil Confederation tribes in the Marib oil-producing area opening the door to salafi and Al Qaeda influence. In southern Yemen, the old People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), the secessionist movement of 1994, reemerged as an independence movement. It covered the spectrum from the Yemen Socialist Party (YSP) which was strongest in the urban Aden area, to tribal oriented elements in Lahj, the Hadramawt, and further east among Mahari tribal groupings. It was in these Sunni areas where the remnants of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula would find refuge and new allies. This 1990 emergence of politicized parties combined with existing political and sectarian friction exacerbated clan and tribal tensions within the society. In addition, the Saleh

family’s neo-colonial exploitation of oil located in eastern Sunni regions, and next-generation rivalries in the Saleh-al-Ahmar alliance created centrifugal forces that destabilized Yemen’s ruling coalition. In combination with other disaffected elements, this instability brought to the fore by the Arab Spring of 2011 undermined Saleh’s 30-plus year rule and exposed the myth of Yemen as a potentially cohesive state.

The Hadi Option 2012–2022: A Decade of Futility

In the aftermath of the Saleh “collapse,” a western-backed and predictably futile effort transpired to find a new political leader and to salvage some form of Yemen unity. It took the form of the so-called “reconciliation movement.” Setting aside the general instability and fractious nature of Yemen politics, this effort had two critical flaws: (1) the reality that key groups had no real desire to be “reconciled,” and (2) the lack of political support for Abd-al- Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, the chosen interim president of a federated Yemen. Saleh chose Hadi as his successor because he was politically weak, and Saleh intended to maintain his control of the General Peoples’ Congress party and his influence within the army. Saleh had not given up.

Thus, the first requirement in understanding the post-2012 political environment is understanding how Abd-al-Rabbuh Hadi fit into the Yemen milieu. A member of the YSP and a PDRY military officer, Hadi was a military officer from Abyan who supported Ali Nasser Muhammad al-Hassani, the President of PDRY, in the South Yemen civil war of 1986. During a PDRY Politburo meeting in January 1986, al-Hassani, backed by the Abyani faction in the government and military, attempted to eliminate the opposition represented by Abd-ad- Fattah Ismail and other rivals. Although he succeeded in killing Ismail and numerous other opponents, he lost the civil war and was forced to flee

to the north. Al-Hassani and his supporters, including Hadi, provided leverage to the Saleh regime in its struggle against the PDRY. In a propaganda gesture to “unity,” he installed the southerners in various powerless government positions. In 1990, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ali Salem al-Beidh, now the head of the Yemen Socialist Party (YSP) and the effective leader of the PDRY, accepted Yemeni unification with Saleh as president. By 1994, the al-Beidh faction concluded that Saleh had no intention of sharing real power, and the union collapsed into Civil War. Al-Beidh led the effort to separate South Yemen from the North once again, and his Abyani opposition led by Hadi supported Saleh’s reconquest of the South. Hadi rallied Abyani southerners to Saleh’s side, tipping the scales in the conflict and enabling Saleh to capture Aden. As a reward, Abyani tribal forces were allowed to sack Aden. For his service, Saleh made Hadi the Vice President of the Republic of Yemen, a position that he held from 1994 to 2012. Hadi provided Saleh with the window-dressing of a southerner in a high-ranking position, but he had no real power base in the north among the Zaydi military, security, and tribal elites.

Among the Zaydi revivalists, Ansar Allah and the “Houthis” in the Sa’ada area, Hadi was viewed as a Sunni socialist pawn of Saleh’s corrupt regime in Sanaa. In the South, he was roundly despised as an agent of northern conquest, a socialist in an increasingly Islamist environment, and the representative of narrow Abyani interests. In 2012, under pressure, Saleh named Hadi as his successor because understanding the weakness of Hadi’s political position, he believed that he (Saleh) could use Hadi to manipulate and maintain control of the political situation in Sanaa. Hadi betrayed him by accepting Western and GCC support to exercise real power in his own right. This move flowed from two gross misconceptions. First, the notion that Hadi could even become an interim step to something viable blithely ignored his political

baggage, and second, Hadi’s own personal and political weaknesses made him unsuitable. As one senior Western military officer noted, “In meetings, Hadi simply could not make a decision.” Perhaps Hadi held some micawberish conviction that GCC and US backing would allow him to consolidate Saleh’s opposition into a viable coalition. He “had become a poster child for radical Islamic Zaydi and Sunni recruitment.” Unfortunately, Hadi had become a malleable, ineffective figurehead around which the West and GCC wanted to mold a new “reconciled” federal state. Predictably, the attempt failed spectacularly in 2014.

In addition to his own political baggage and personality traits, Hadi had another liability – Saleh. The former, or shadow, president controlled the General People’s Congress Party (GPC), and used the billions siphoned from the Yemeni government and oil reserves to maintain the loyalty of key elements within the Yemeni army and bureaucracy. Always a player, Saleh was determined to undermine the “reconciliation” movement and eliminate everyone that had betrayed him. It was a long list — the US, Saudi Arabia, the GCC, the Hashid al-Ahmars, various political groups and last, but certainly not least, Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi. In a surprise, but predictable, move, Saleh allied himself and those army units loyal to him with the Houthi family and Ansar Allah. Saleh’s version of a “reconciled” Yemen would give this new coalition access to the coast and oil revenues. Saleh facilitated the capture of Sanaa through combining army units loyal to him with Houthi forces. Saleh dethroned the al-Ahmar clan and its allies and removed Hadi’s interim government, successfully defying the West and all who had assisted in his ouster. No doubt Saleh believed that he would deal with the Houthis at some later date. It was to be a replay of the 1994 conquest of the south with a different combination of players, but with Saleh still a major powerbroker, if not the sole leader.

Yemen: The Arab Gulf and Western Interests

At this point, the GCC, led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and backed by the US, intervened. This intervention, sparked by fears of increasing Iranian involvement with Houthi Zaydi revivalists and 30 years of distrust of Saleh, reflected Saudi Arabia’s preference for a weak, divided Yemen that reflected its political, economic, and socio-cultural differences. Saudi Arabia consistently opposed the unification of Yemen from the time of the rise of the Third Saudi State (1902–1932) to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (1932–present). This opposition was grounded in real security concerns, particularly regarding foreign intervention in Yemen and Yemen becoming a base of operations for opponents of the Saudi states. During the 1930s, the Yemeni Imamate fought a series of border wars with the kingdom that resulted in the Treaty of Taif (1934) in which the Imamate ceded Asir and Najran to King Abd-al-Aziz bin Abd-al- Rahman al-Saud (Ibn Saud). During the Yemen Civil War (1962–1969), Saudi Arabia openly, and the British surreptitiously, supported Imam Badr and the northern Zaydi tribes against the revolutionary government of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) backed by Nasserist Egypt. After a purge of leftist and socialist officers from the Yemeni army in the 1970s, the kingdom backed the YAR government, and the al-Ahmar’s dominated Hashid tribal confederation against the socialist PDRY government in the South. No matter what the configuration of the alliances, Saudi policy for the last century has reflected the fundamental understanding that Yemen was a fractured political pseudo-state dominated by its tribal topography and a strategic threat to Saudi Arabia. For that reason, outside elements attempting to gain influence, whether the East-Bloc during the Cold War, Nasserist Egypt, or the Islamic Republic of Iran, were to be thwarted. In 1990 and 1994, Riyadh strongly opposed the unification of Yemen, while the US and the West hubristically ignored Al Saud advise and warnings.

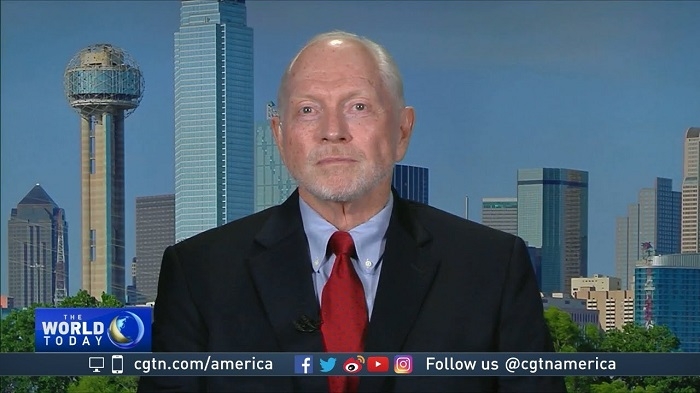

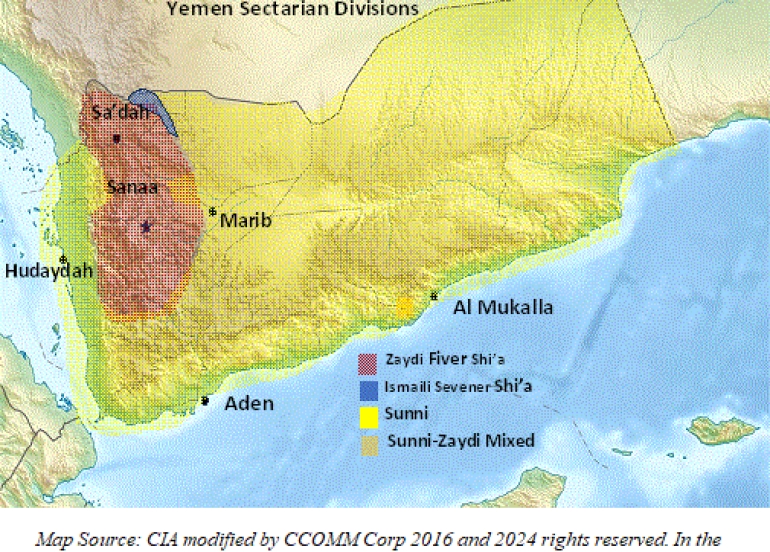

A second and almost equally important element drove Saudi and UAE policy. Except for the central region, roughly bordered by Ibb, the Wadi Jawf, the north-south coastal mountain spine, and the Saudi border to the north, the “Yemens” are arguably Sunni. In the Mahrib province, the tribes made no secret of their allegiance to Riyadh— they were fundamentalist or Hanbali Sunni tribes. On the west coast, the Tihama, the tribes and towns people were distinctly Africanized Shafi’i Sunni, and it was an area that the Wahhabi emirs of the First Saudi State controlled for decades even after its collapse. In the south and east, the British protected Sunni tribal and Adeni urban autonomy from Zaydi expansionists. The south-central region around Taiz and Ibb constituted a contested area in which the Zaydi imams of the north combined cooption and repression to maintain tenuous control. The Sunni-Zaydi divide was also reinforced over the centuries by formal agreements. The treaty of Dan in 1902 between the Ottoman Turks and the Zaydi imamate recognized the Imam’s authority in the regions from Ibb to Sa’ada in the north, but confined it to the central areas. In the aftermath of World War I, the Imam Yahya used Ottoman troops now in his employ to take control of areas that had never fallen under the sway of Zaydi Yemen, fundamentally turning the Tihama and southern uplands centered on Taiz into conquered territory.

Between 1990 and 1994 flush from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the first Gulf War, the mirage of Yemeni stability drove Washington to support the creation of a “nation-state.” The 1990 “unification” of Yemen, followed by the 1994 “conquest” of the south by Saleh, created the illusion of a Republic of Yemen and appeared to fulfill a naïve US narrative that Yemen was or could become a “state” and that Saleh could be a segue to a new pluralistic political

future governed by rule of law. The actual situation and results were quite different. Those policies brought a secessionist movement in the south, AQAP in the various regions, and the Zaydi revivalist Houthis of the north with their Hezbollah-want-to-be ambitions. These developments intensified the political chaos of 2011–2012. Should the Saleh-Houthi alliance have reconquered Sunni Yemeni, the situation would likely have been much more inimical to Gulf Arab and Western interests and even more unstable. Thus, the partially successful Saudi-GCC campaign to restore the Sunnis to their dominant place on the Yemen littoral and confine Zaydi revivalist influence to the central mountainous region produced a result that was better than the alternative. Despite Western and GCC efforts, the Houthi-Saleh alliance managed to take control of the Tihama region and the northern Red Sea coast. Prior to Saleh’s regime, ties between the Tihama and Zaydi north were almost non-existent; however, YAR government policy sponsored population shifts from the uplands to the coast, expropriation of land, and occupation by Zaydi military and security forces. Saleh and the Houthis needed to maintain access to the Red Sea to prevent their isolation in the uplands. Sans Saleh this access has become even more important to the Houthis because it provides a conduit for Iranian aid. The ability to hold the coast and Hodeidah is now the geopolitical core of the problem posed by the policies of the Houthi clan.

The Current Political and Military Reality

This brings the discussion to the political-military situation of 2024. While “reconciliation” failed, the Hadi experiment failed, the GCC bombing campaign failed, and the Houthis and their allies were prevented from taking the south, nothing has fundamentally changed in how Yemeni politics work. In the current situation, a political equilibrium can only emerge as a function of military

leverage and the threat posed by internal Yemeni developments that potentially undermine the leadership of the Houthi clan. Historically, Zaydi regimes in Yemen have come to the bargaining table when their access to the coast has effectively been denied. Arguably from the 13th through the 20th centuries, Zaydi polities came to political accommodations as a direct result of denied access to the Red Sea. Multiple examples during the Ottoman period include a period of Wahhabi control and influence where accommodations with the Zaydi rulers or tribes flowed from outside control of the western coast – Hodeidah as a necessary starting point for control or influence in Sanaa. In the 1930s, Saudi Arabia brought an end to a border and gained a treaty annexing Asir and Najran by occupying the Tihama. In each case, the military situation required ground forces in conjunction with indigenous Sunni resistance to force the Zaydi imamate to come to terms.

These goals face a series of obstacles. First is a shift in strategic perspective on the threat. Expansion of Iranian influence on the Arabian Peninsula is the strategic threat to Western and US interests. US policy is no longer a function of placating GCC allies in the region; it is a matter of direct US strategic interests. This fact was debated a decade ago, but it should be undeniably obvious today. AQAP and other Sunni jihadist groups constitute an ongoing security problem, but not a strategic threat to Western interests. The current situation in Yemen threatens the stability of the Arabian Gulf, the entire global energy market, and international trade of which the US and its Western allies are the major beneficiaries. The situation that has developed also requires that Western policy makers take a longer, broader view of the challenges and potential solutions—the policy choice is not between diplomacy and military action, but rather it is a combination of military action and diplomacy and other means to achieve strategic political goals. Evidence of this reality has begun to seep into policy execution.

Second, a concrete recognition that Zaydi domination of traditional Sunni regions is a significant irritant driving radical Sunni jihadist movements is a requirement. ISIS, Al Qaeda, and the like only survive in Yemen through arrangements with disaffected Sunni groups. Rivalries between various Sunni political and tribal groups are challenging enough, but when the additional pressure of a revivalist Zaydi threat is added, there is a propensity to accept help from any source including those accused of association with notorious terrorist affiliates. Third, there are military risks involved in a campaign to restore the Tihama to Sunni control. The US’ Gulf Arab allies have learned some useful lessons since 2014. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE lack the ability to prosecute a ground war anywhere, much less Yemen. Their military forces are designed for regime protection, not power projection. Technological superiority will only go so far in a relatively primitive setting. Mercenaries and proxies are about getting paid – not dying for the cause. Expect no unilateral repetition of Prince Faisal’s 1934 occupation of the Tihama and Hodeidah or a push to Sanaa through Marib. Significant casualties brought a complete change in strategy from Abu Dhabi and effectively ended the Saudi-UAE alliance, and attempts to find surrogates brought other problems. Mercenaries balked when confronted with the prospect of mountain operations or a house-to-house fight for Hodeidah. The attempt to enlist the Egyptians fell flat — the Egyptians had one prolonged, bad experience in Yemen 1962–1968 and decided to sit this campaign out. The Pakistani’s also demurred supplying cannon fodder for a price. Then, domestic security concerns or ideological predilections entered the equation — the UAE was picky about its allies eschewing any groups who smacked of Muslim Brotherhood or al-Islah connections while at the same time having to carefully dodge any association with Al Qaeda or ISIS elements. To his credit, Mohammed bin Zaid Al Nahyan, the ruler in Abu Dhabi, recognized the UAE’s limitations and changed its mode of operations in Yemen, effectively withdrawing from its alliance with Saudi Arabia and shattering what little Gulf Arab cooperation existed. After all, Saudi Arabia shared a border with Yemen, and the UAE did not. The idea that US or Western ‘main force’ units might be employed is a non-starter.

Third, these ‘fissures’ are not just Sunni versus Zaydi, but in fact more often include intra-clan and tribal conflicts within the larger political and religious groupings. Ideology notwithstanding, the primary motivations that continue to underlie the socio-cultural structure of Yemen are family, clan, and tribal ties with ideology taking a distant second. Every political group in Yemen is vulnerable to this including the Houthi clan. Fourth, the most difficult change in mindset in dealing with Yemen is accepting and operating in a chaotic environment where solutions per se simply do not exist. Yemen cannot be ‘fixed.’ The militancy, humanitarian crises, corruption, and lack of development, etc., are the givens within which policies and actions must be periodically taken to prevent Yemeni chaos from spilling over into the region. Unfortunately, concerted political efforts, military action, and even humanitarian programs with strings may put even more of the Zaydi population at risk by depriving the Houthi regime of outlets to the sea and by encouraging civil strife to moderate their policies. Such an effort requires a more dedicated approach to dealing with Yemen – not necessarily in terms of numbers, but in terms of longer-term commitments of diplomatic, intelligence, and military personnel who actually become Yemen experts as opposed to just serving one to three-year tours. In addition, higher risks for effective but minimalist special operations on-the-ground efforts like those in Afghanistan 2001–2002 must be accepted as the price to be paid for dealing with the current situation and anticipating the next one.

In a risk-benefit analysis, the continued domination of large parts of Sunni Yemen by the Zaydi north has been a recipe for instability in the Gulf, Iranian meddling, the creation of a Hezbollah-like entity, and the continued expansion of radical Sunni jihadist movements. The reestablishment of Sunni autonomy in traditional Sunni areas would serve to isolate any regional threat posed by Zaydi revivalism. It would inhibit, if not end, Iranian adventurism and might well result in more moderate policies from Ansar Allah itself, with or without the Houthi clan. It might provide a pathway to a more stable, albeit fractured, political, economic, and social structure in Sunni Yemen and put pressure on the Zaydis to cooperate within a political framework that allowed for Zaydi autonomy. None of this would happen overnight, but the previous view of a “reconciliation” was fundamentally flawed, and the current situation is unacceptable. Saleh’s state, and for that matter that of the Imams, was anything but unified; however, they provided more stability than the current arrangement. The Houthi clan needs to be encouraged to focus on internal problems as opposed to using ideology as the primary tool for survival. How might this be accomplished?

Clausewitzian “Political” Whack-a-Mole as an Enhanced Strategy?

Arguably, the West, and for that matter Saudi Arabia and the UAE, finds itself in much the same position that it faced in 2016-2017 with some exceptions. On the plus side, “reconciliation” is dead and the Hadi albatross is hopefully history. The new Presidential Council under the chairmanship of Rashad al- Alimi is a step in the right direction if for no other reason than the council appears to have disabused itself of pretentions to any comprehensive solution. The “hybrid sovereignties” serve as a recognition that Yemeni central state authority does not exist, and that political arrangements must function within this reality. It defines Yemen as a collection of “micro-states” lacking in any cohesiveness.7 This is a significant step forward opening the door for “micro” settlements of some issues but also providing a window through which direct Western and US participation with permanent or semi-permanent in-country elements should create more visibility into the granularity of the conflicting groups and pathways for pursuing Western interests. The situation also opens the door to new Western Yemen-centric thinking regarding specific problems. In a Clausewitzian political environment, there is no difference between diplomatic, military, or subversive approaches – all constitute parts of an overall pathway to a “political objective.”

In this regard, the current Western raids targeting drone and missile launching sites and munitions storage facilities reflect a more Yemen-like approach to problems. Alone this is no more likely to succeed than the earlier US-backed Saudi and UAE bombing campaigns, but coupled with SOF operations on the ground, the combination is a step in the right direction. The earlier bombing campaign may have failed to impose a solution on Ansar Allah and its Houthi leadership, however, the Saudi-UAE intervention in the south demonstrated to the Zaydi revivalists the limits of their power. With significant areas of the south and east, including most of the oil producing regions, largely out of reach of Houthi control, that intervention for all its stops and starts and questionable applications of ideological proclivities has been at least partially successful. The current stalemate on the ground has created the opportunity to apply a more sophisticated, multi-faceted approach to current and future problems.

There are ‘givens’ at the present time. First, Ansar Allah and Zaydi revivalism and the Houthi clan leadership are a current reality — the former, likely for the long term, and the latter, to quote Saleh, for as long as they can “dance on heads of snakes.” That said, what is currently perceived as Houthi control or Zaydi unity is to one degree or another a byproduct of the Saudi/UAE proxy military campaign and particularly their air campaign against Ansar Allah with its well-publicized missteps — school buses, weddings, etc. The campaign created a siege mentality among divergent Zaydi groups, and some Sunni groups as well, and elevated the importance of Iranian aid. Having witnessed first-hand the general disdain in which the Sa’ada-based Zaydi tribes are held in the Ibb, Taiz, and Sanaa regions, the Houthi clan no doubt faces more centrifugal forces and needs the distractions of Gaza and Sunni threats to detract from the horrendous situation in areas that they control. The Houthi clan’s attempts to become the successor to the Imamate tradition or even Saleh, who was himself from a Zaydi tribe, would create exploitable tribal and factional frictions and challenges. From a Western perspective, it is immaterial whether the Houthis or some other group control Upland Yemen as long as they are not making an international nuisance of themselves. The Zaydi regions have no resources and little prospect of economic viability without aid. Historically, Saudi aid floated both the Saleh regime and the Zaydis. Iran can meddle and provide military support, but substantial financial support is another issue. Rival elements within the Ansar Allah movement might prefer an arrangement with Riyadh or broader GCC that ensured financial support without political and military liabilities associated with Iran. These possibilities need to be thoroughly explored.

For its part, US efforts on the ground have been hampered by policy and operational guidelines. For reasons of capability and/or politics, Washington eschews operational risks and relationships where they might be accused of association with Sunni jihadists. Political and ideological considerations have trumped pragmatism – the Middle East maxim is ‘the enemy of my enemy (at least for now) is my friend.’ Drone strikes and kinetic SOF operations that are dependent on second-hand and third-hand intelligence from indigenous sources via Arab allies are at times necessary, but risky. The US needs intelligence from “informed” assets imbedded in the political, military, and socio-cultural realities of the situation. Political concerns have tended to undermine the US’ ability to become more directly involved with groups who might otherwise provide an ally against Ansar Allah. In Yemen, dealing with problems often includes associations with those that one might otherwise choose to avoid. For the US and the West to exploit this fractured human topography, a level of analytical expertise and experience on a variety of subjects, including the tradition of Islamic revivalist movements, tribal nuances, and the identification of leadership proclivities, is essential. To date, the lack of any significant policy consistency or even modest success indicates that the West simply does not possess this capability.

The fractured situation across the Middle East and pointedly in Yemen requires some rethinking in the West about interests and policy proclivities. The two most significant events of the last 50 years in the Middle East, the 1979 rise of Khomeinist Iran and 9/11, have colored Western policy in general and US policy in particular. This situation contributed to policy “small ball” and the attendant disasters in Iraq and Afghanistan. It undermined the ability of the US to conduct the kind of pragmatic, opportunistic policies that had benefited the West in the Middle East during the Cold War. On the one hand, the US was adamantly opposed to Khomeinist Iran and Shi’a fundamentalism, and on the other it declared a Global War on Terror (GWOT) focused on Sunni salafis. The politics of ‘protecting the homeland’ overshadowed the strategic importance of pragmatically and ruthlessly enhancing US strategic interests, thereby “protecting the Homeland.” The US lost much of its ability to effectively play one group against another. The obsession with the serious but nevertheless tactical threat posed by Islamic terrorism skewed more strategic judgements about the utility of Salafists as a tool in pursuing strategic goals.

Religious fundamentalists, evil or benign, are potentially useful depending on time and place even if they become a problem at some future point. It was the war that the US practiced in Afghanistan against the Russians and then against the Taliban in 2001–2002 with spectacular success. The ultimate failure in Afghanistan resulted from attempting to remake the society in a Western image as opposed to ruthlessly pursuing the game by Afghan rules. The current Yemen situation requires the recognition first and foremost that the nature of Yemeni society and politics cannot be changed; therefore, there is no “solution” to the instability and humanitarian problems — there never has been and never will be. The West needs to seek narrow outcomes to specific problems that will likely be temporary. Yemen, like Afghanistan, cannot be fixed, but as the US proved in 2001–2002, problematic groups can be undermined and even eliminated when their rivals receive timely help and encouragement. It is not a diplomatic problem or military problem or intelligence problem; it is a Clausewitzian political problem that requires the coordinated application of pressure in all three areas. Success will always be limited and lead to another challenge, but creating an environment where the Yemeni focus turns inward is the best that can be hoped for.

Analytically and, to a certain degree, operationally, the US is largely dependent on ‘experts,’ many of whom have never been to Yemen or have only seen it from a fortified compound; have never seen Sa’ada, Marib, or Taiz or had a conversation with a Zaydi jabili from the north or a Bedu from the Ramalat al-Sabatayn; or grappled with the vicissitudes of tribal politics and conflict in the Central provinces and south. As a result, some of those experts argue that Zaydi Fiver Shi’sm and Khomeinist Iranian Shi’sm have become indistinguishable, reflecting not only a superficial understanding of how Islamist revivalist movements work but also a lack of appreciation for that fact that in a tribal society personal, family, clan, tribal ambition, almost always trumps ideology. The verbiage or façade of ideology may change but the nature of the society and the people remain remarkably consistent.

For on-the-ground political and military operations and initiatives, the US policy of rotating military, diplomatic, and intelligence officers precludes the development of military and political officers like Sir Lewis Pelly or Sir Percy Cox, both of whom spent decades as hands-on British military and political officers in Arabia and the Gulf. Perhaps the US needs to develop its own 21st century “residency” system – call it what you may – to better deal with the complexities of the fractured political reality of the region. Such experts would combine the skill of intelligence, military, and diplomatic officers and be dedicated to a region or focused on a specific problem. In places like Yemen, the country-team concept based on the State Department, an embassy, and an ambassador may, in fact, be dead. The situation and the person, not some bureaucratic policy decision from the Eisenhower era when John Foster Dulles headed the State Department and Allen Dulles headed the Central Intelligence Agency, should determine the lead in situations where state institutions no longer exist. Like it or not, it should be obvious to all that we are invested in the Middle East for the long-haul or at least the next 40 years. In the case of Yemen, we cannot save the Yemenis from themselves. The West cannot care more about famine, overpopulation, corruption, violence, agricultural issues, and develop- ment than someone like Abd-al-Malik al-Houthi. He knows that he cannot fix Yemen’s problems and exploits them for the benefit of his own family and clan. Houthi Yemen introduces an unacceptable level of instability and disruption into a system of global trade that benefits the West – the US needs to focus on protecting itself and its allies from that, not on Yemen’s endemic problems that will never be solved. As for the role of Iran in Yemen, this is a part of a broader question – how to deal with Iran. The Iranians have taken the official position that they do not want to see a broader war in the region and have stated that they are attempting to rein in their proxies. The former is likely correct, but the latter is more likely a façade behind which Tehran continues to support those who actively attack Western and Gulf Arab interests. Ultimately, the US will have to make a strategic decision that includes exploiting Iran’s own internal divisions and weaknesses. Iran or Persia has a long history of limited periods of autocratic rule and stability punctuated by extended periods of currently overdue instability.

Conclusion

Given that Yemen cannot be ‘fixed’, the primary question becomes the price of alleviating the aggravation. To a significant degree, the source of the current aggravation is Iran. Tehran has found value in using the Houthi clan’s current dominance in the Zaydi Revivalist movement, i.e., Ansar Allah, as leverage on the Arab Gulf and particularly on Saudi Arabia and the UAE. October 7th has provided both the Houthis and Iranians another ‘cause’ where they can demonstrate their ideological commitment to supporting the Palestinian people. It is a proxy war pure and simple; and for the Ayatollahs it is far better to have the US and its allies dropping bombs on the Houthis as opposed to infrastructure, weapons production, and nuclear sites in Iran. To the Iranians, Houthis, Palestinians, Alawites, Hezbollah, and various Shi’a groups in the Greater Levant are merely tools to be used in the process of reclaiming Iranian (Persian) influence, power, and prestige in the region. That poses the question for Yemen and for broader Western interests from the Gulf to Ukraine – ‘Has the time come to really address the Iranian issue?’ Presently, the official answer is no. Micawberish optimism (or delusion as the case may be) might miraculously prevail. Perhaps it will be in the form of internal stress collapsing the Islamic Republic, or there could an epiphany on the part of the Guardian Council that their current policies and those of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are not only counterproductive in terms of Iranian interests but will also ultimately lead to ruin. Without some significant encouragement, though, this is highly unlikely. Sooner or later, the Iranian issue will have to be addressed in a more dramatic fashion. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, the West “always does the right thing after it has tried everything else.” At the present time, there are more pressing issues in Europe and the Far East, creating a reluctance in Washington to go to the source of the problem. As a result, the West is unfortunately left to deal with the localized situation in Yemen.

Influence in Yemen flows from unsparing pragmatism and flexibility. Tunnel vision on a particular regime or individual leader is virtually guaranteed to fail. Yemeni proxies are driven by their own fluid agendas and interests; thus, Western policy must be based on multiple groups and points of leverage. Every group in Yemen has enemies that can be exploited by the ruthless application of the maxim ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend for now’. Between 1945 and 1979, US involvement in Yemen was characterized by a studied effort to avoid entanglement. Washington largely turned a deaf ear to British efforts to get US cooperation in offsetting Nasserist and Soviet influence in the Imamate. Even in the face of Egyptian air raids on Saudi Arabia, and ironically their Zaydi allies, and Soviet and Chinese military and economic aid, the US avoided serious involvement and even went so far as to recognize the Nasserist, anti-American puppet regime in Sanaa. This situation provides a template of sorts for one approach to the current situation in Yemen – recognize the Zaydi regime and its Houthi rulers. Frankly, the recognition of Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) was something of a naïve last-ditch effort by the US ambassador in Cairo, John Badeau, to preserve not only his position in Cairo but also his waning influence within the Kennedy administration.8 It was a mistake providing little or no upside in Cairo and none whatsoever in Sanaa. It failed to prevent the Yemen Civil War or the revolt in Aden; recognition should have been withheld for a larger quid pro quo. It serves as an object lesson for the situation today. Within six years, the Nasserist regime in Sanaa and most of its leadership was history replaced by a regime more acceptable to both the West and Saudi Arabia. Ipso facto, there is no reason to even consider recognition of the Houthi-led regime. A second object lesson flows from this experience. Support for the narrow clique of leftist military officers in Sanaa was far more ephemeral than they or their opponents understood. The protracted civil war, driven by an alliance between Saudi Arabia and Zaydi tribes of the north and supported by a small but potent contingent of British and Jordanian Special Forces, fought the better equipped Egyptians and their Yemeni allies to a standstill while undermining support for the regime. In the end, it was personal, family, clan and tribal loyalties that undermined the Egyptian effort. The crowning blow to the first YAR government and its Egyptian backers happened not in Yemen but in the Sinai. The disaster of 1967 in the Sinai left the Egyptians with no alternative but to withdraw their forces and reduce their aid from the regime in Sanaa and, by 1969, created the conditions for unstable but tolerable political compromise. Would Egyptian priorities have changed had it not been for 1967? Eventually. The real issue was the inability to impose a “solution” because of Yemeni factionalism. Cairo did not so much lose as they realized that in Yemen no one can win. The alignments may have changed but the situation is hardly any different. The Houthis represent a narrow, clan-based ruling clique with a neo- Zaydi ideology. Within the Ansar Allah movement, they have internal rivals. Within Yemen, they have sectarian and political enemies, and they have a single external benefactor with its own set of pressures and priorities. They are vulnerable to coordinated support for their Zaydi rivals and insurgencies by their non-Zaydi enemies, the application of whack-a-mole Western military intervention, and their own failure to improve the economic and humanitarian crisis. There is also the possibility that their benefactor might decide that continued financial and military support is counterproductive to its own interests.

The West has no interests in Yemen other than limited regime behavior modification. In that regard, it needs a coordinated effort including limited direct military involvement that utilizes political, military, sectarian, economic, and social pressure to encourage the Houthi regime or its opponents that aggressive expansion of territorial control or attempting to disrupt international trade is not in the best interest of any Yemeni group. It is not a ‘solution’ – it is merely an attempt to partially stabilize an unstable situation. Even a temporary solution will take time and persistence to realize; however, in an increasingly fragmented world, it could provide a template for the future as political sovereignty becomes an increasingly scarce global commodity. If the US could forget its obsessions with Westphalian myths, nation-state development, socio-cultural trans- formation, and notions of greater ethical and humanitarian responsibility, we know how to conduct multi-pronged Clausewitzian political campaigns in a relatively affordable fashion. We need to practice that in contemporary Yemen while mindful that the goal is not a ‘solution,” but rather it is to maintain an acceptable level of instability and volatility consistent with Western interests.

About the Author

Dr. Roby C. Barrett is former Foreign Service Officer with an intelligence and special operations background and served in North Africa, Yemen, the Levant, and Arabia. He is a Scholar and Gulf expert with the Middle East Institute, Washington, D.C. He was a Senior Fellow at the Middle East and North Africa Forum at Cambridge University and the author of MENAF’s “Series on Gulf Security” in Manara magazine and a former member of the advisory board at the Defense Language Institute. Barrett is the author of numerous books and articles on the Middle East and Southwest Asia including The Cold War in the Greater Middle East: U.S. Foreign Policy under Kennedy and Eisenhower (2007) and The Gulf and the Struggle for Hegemony: Arabs, Iranians, and West in Conflict (2016).

Originally trained as a Russian and Soviet expert, Dr. Barrett is a was the Arab Gulf team leader in the Office of National Intelligence simulations on Russia in the Middle East and a keynote speaker at Joint Canadian-U.S. Intelligence Conference on Iran and Gulf Security in Washington, D.C. As a Senior Fellow with the Joint Special Operations University, U.S. Special Operations Command, he authored eight monographs on the Middle East and Islam as well as serving as an Instructor of Applied Intelligence. He also served as a briefer and subject matter expert for Special Operations-U.S. Central Command and for the Middle East Orientation Course at the Air Force Special Operations School where he was also a Senior Fellow. He has provided support to the Office of Secretary of Defense, the National Defense University, the Office of National Intelligence, the State Department, and other security and intelligence organizations.

Dr. Barrett was a visiting professor at the Royal Saudi Arabian Command and Staff School focused on Gulf security, specifically Yemen and Iran, and a featured expert on Iran at the German Council on Foreign Relations and with the Bundeswehr. He has spoken at numerous Middle East conferences including the Bahrain MOI Gulf Security Forum, the opening of the King Abdullah Special Operations Training Center, the Arabian Gulf SOF Conference as well as the UAE security conference. His business expertise focuses on technology integration in intelligence and security operations and applications. He was Vice President for Air Force and Special DOD programs at Electronic Data Systems and a Corporate Vice President for Special Programs at Science Applications International, where he also served as Special Assistant to the Vice Chairman of the Board. Barrett specializes in security operations technology and integration.

A recipient of the Eisenhower-Roberts Fellowship from the Eisenhower Foundation, Dr. Barrett held research and study fellowships at the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich and at Oxford University. He is a graduate of the two-year Middle East Studies and Arabic Language program at the Foreign Service Institute, Washington, D.C. and Tunis, Tunisia, and holds a Ph.D. in Middle Eastern and South Asian history from the University of Texas at Austin.

1 Frederick D. Lugard, The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1922). This is the definitive defense of British colonial rule in Africa specifically, but it also applied to other British colonies by its most eminent practitioner. Lugard conceded that British methods had not produced ideal results everywhere, and that pure philanthropy could never be the only motive of empire, yet the welfare and advancement of African peoples was a strong guiding principle of British rule, part of its "dual mandate" of reciprocal benefit. Where native races were becoming restive, he declared, it was precisely because of their exposure to British values of liberty: "Their very discontent is a measure of their progress." The arguments are also reflected in progressive justifications for US intervention in places like the Philippines and attitudes about nation building that come from the American progressive traditions of the 19th century. The idea is that if we can make others think and act like us, then the resulting spread of Western style liberal democracy will create global peace and prosperity. It also touches on what has been described as Salvationist discourse. This is the idea that the “superior’ West has a greater responsibility to introduce or to compel others to develop liberal democratic institutions and to adopt Western humanitarian ideas.

2 In the United States, this idea of a take-off point at which economic development would initiate a period of political liberalization was particularly associated with the Charles River School of political-economic thought, the proponents of which became closely associated with the Kennedy Administration and global competition with the Soviet Union and the Marxist-Leninist approach to economic modernization and the exercise of political power. For all its flaws, it was an attempt to provide a rational ideological alternative to Communist propaganda and “liberation front” authoritarianism. Unfortunately, what sounded good in theory did not fit the reality of the developing world – the US experience in Vietnam demonstrated this disconnect.

3 Jan Retsö, “When did Yemen become Arabia felix,” Seminar for Arabian Studies 33 (2003): 229–235. The term applied to any fertile area of Arabia and first applied to the coastal area opposite Bahrain. It was called Arabia eudaemon. In the 19th century, European explorers translated the term inaccurately from Roman accounts. The only reason this is important is that it fueled a romantic notion that at some period in its past Yemen was a “happy” place in Arabia – a spurious idea.

4 See Neil MacFarquhar, “Tahseen Bashir, Urbane Egyptian Diplomat, Dies at 77,” New York Times, June 14, 2002. Tahseen served Nasser and Sadat and thoroughly harassed Mubarak. Urbane, well-educated and well read, was famous for memorable political phrases. Two of the more memorable were “the mummification of the Egyptian cabinet” and “Egypt is the only nation state in the Arab world, the rest are just tribes with flags.”

5 Robert D. Burrowes, The Yemen Arab Republic: The Politics of Development 1962–1966 (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1987): 8. Sally Ann Baynard, Laraine Newhouse Carter, Beryl Lieff Benderly, and Laurie Krieger, “Historical Setting,” The Yemens (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1986), 35. See also, Daniel Martin Varisco, “Texts and Pretexts: The Unity of the Rasulid State under al-Malik al-Muzaffar,” Revue du monde musulman et de la Mediterranee (Vol. 67, 1993): 13–24.

6 Patricia A. Risso, Merchants and Faith: Muslim Commerce and Culture in the Indian Ocean (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995): 45–47. See also, Daniel Martin Varisco, “Texts and Pretexts: The Unity of the Rasulid State under al-Malik al-Muzaffar,” Revue de monde musulman et de la Mediterrance (Vol. 67, 1993):13–24.

7 Eleonora Ardemagni, “Yemen’s Post-Hybrid Balance: The New Presidential Council,” Carnegie Endowment for the Humanities, June 9, 2022: http://caregieendowment.org/sada/87301.

8 Roby C. Barrett, The Gulf and the Struggle for Hegemony: Arabs, Iranians, and the West in Conflict (Washington, D.C.: The Middle East Institute: 489–493. See also Barrett, The Greater Middle East and the Cold War: US Foreign Policy under Eisenhower and Kennedy, (London: I.B. Tauris Press, 2009).