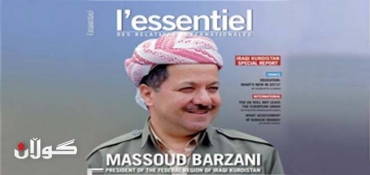

Interview with President Masoud Barzani

L’Essentiel des relations internationales: How extensive has the repression of the Kurdish people in Iraq been?

Masoud Barzani: Repression of the Kurdish people goes back a long way, but the situation deteriorated after the First World War. It became systematic. It went up several gears to reach its full horror under Saddam Hussein, when he conducted his “Anfal” military campaigns. A figure of 182,000 victims is currently accepted by the international community. Five thousand people were killed in the chemical bombardment of Halabja alone, four thousand in chemical attacks on the rest of Kurdistan. Fifty thousand peshmerga martyrs fell in the struggle against the regime, and 200,000 were wounded.

As leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), you signed an electoral agreement in 2004 with the other major party, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), of which the President of the Republic of Iraq, Jalal Talabani, also a Kurd, is a member. What is your assessment of this agreement from a political point of view?

We are firm believers in the need for coexistence and cooperation between Kurdish forces. We have experienced a civil war – between our two parties – but that is now in the past; we have moved on. To ensure the defence of an autonomous Kurdistan, cooperation between the KDP and the PUK is essential. One of the most important aspects of this agreement is that, while preserving the distinct identity of each party, it enables us to speak with a single voice, that of the Kurdish people. The results are evident everywhere: we are experiencing an economic boom, the construction industry is flourishing, and we have security.

And where the functioning of institutions and democracy are concerned, what progress has been made since you were elected to the presidency by parliament in 2006?

We are still in the early stages. Much remains to be done and we admit that we are inexperienced where governance is concerned. We are in the process of building our institutions as set out in the constitution and establishing a separation of powers between parliament, the courts and the executive. Another of our objectives is to guarantee individual freedoms. We are proud of the fact that there are no political prisoners in Kurdistan. We are encouraging the emergence of representative organisations within civil society. There are currently 1,300 non-governmental organisations, a considerable number in a country as small as ours.

As you see it, what difference was there between the 2006 elections – when you were elected President by the Parliament – and the Kurdish presidential elections of July 2009?

Between these two elections, there was no change in the attributes of presidential power, which are in any case set out in our constitutional law. When I was asked to run for the Presidency, I told Parliament and the parties that I was willing to do so if the election was to be by universal suffrage. But if the President was to be elected by Parliament, I would prefer someone else to run in my place. I needed to know exactly how much support I had from the people, not just from members of Parliament. I wanted to know what percentage of people were for and against my election. The members of Parliament who vote for you are constrained by various obligations, which is not true of the people. I needed the legitimacy that comes from the people.

What measures are you taking to ensure that the younger generation, who are an essential component of civil society, can achieve the living conditions and cultural standards of developed countries?

Ours is a very young society, with 59% of the population under 25 years of age. It is therefore our duty to educate them and give them the chance of a better life in the years ahead. They are the future of Kurdistan. We now have seventeen universities, in which education is free of charge. Thanks to our scholarship programme, 5.000 Kurdish students so far have had the opportunity to continue their curicculum abroad. Some of them are studying in France. We have a system for providing finance and small loans to our Youth who want to set up their own businesses. Once they have received their diploma, students are paid a benefit until such time as they find work. We encourage students to go into the private sector and take care to ensure that their salaries are in line with those of civil servants.

A problem has arisen recently between you and the central Iraqi government over oil production. Mr Hussein Chahristani, the minister for oil resources in Baghdad, reacted somewhat aggressively to the signature of separate contracts between the Total Group – which has acquired 35% of the Marathon Oil Group’s production licence – and the government of autonomous Kurdistan. How has this affected relations between you and the Federal Republic of Iraq?

We have not overstepped our constitutional prerogatives. One of the principles of the Iraqi constitution is that oil and gas resources belong to each and every Iraqi. This principle is widely supported. In February 2007, we agreed to a joint project concerning oil and gas resources. This project contains an appendix giving us the possibility to sign oil contracts if by May 2007 the draft text hasn’t been adopted by Parliament. The other argument to the effect that what we are doing is unconstitutional or illegal, or not within our powers, is unrealistic. It is illogical to believe that Exxon Mobil, Gazprom, Chevron or Total would get involved in a disputed territory (Kurdistan – ed.), where they are not entitled to exploit oil resources. It is public knowledge that Kurdistan’s oil production policy has been a success. Meanwhile, the minister responsible for oil production in Iraq has failed in his task. All he is doing is showing his hostility towards the Kurds. He would do better to concentrate on the electricity supply in Iraq.

Differences with the central government are increasing. You have many times called on the Iraqi government to respect Article 140 of the Constitution (referendum on the attachment of Kirkuk to Kurdistan – ed.). What is the current situation?

One of the most important matters still to be decided on and worked out within Iraq is indeed this article of the Iraqi constitution. In agreeing to this article, we had no doubt about Kurdistan’s vocation to remain autonomous within the framework of the law. We believed, and continue to believe that this article can be implemented with international support. We thought, and still think, that the Kirkuk region should be re-attached to Kurdistan. This article is about a normalisation: a population census and referendum. We have never claimed a right to impose our own solutions where the application of this article is concerned. The people of the Kirkuk region should be free to decide their destiny in a referendum. But, unfortunately, the Iraqis have done little to put this article into effect. They are procrastinating. We believe that the application of this article is also in the interests of Iraq.

We are currently seeing a strengthening of the sense of Kurdish identity in Syria, with some Kurds fleeing to autonomous Kurdistan to escape the fighting. Do you think that an Iraq-type solution might be applicable in Syria? Would you be in favour in the longer term to the reunification of the two Kurdish entities?

The situation of the Syrian Kurds is different, because they have been deprived even of citizenship. They have not been treated as citizens of their country. And the process of arabisation began much earlier, in the early 1960s. Many children have been obliged to attend Arab schools. Each part of the Kurdish people has its own specific circumstances and characteristics. The solutions for the different areas in which they live must therefore be different, too. They need to be in keeping with the realities of the countries in which the Kurds live. We cannot export our Iraqi model to Syria, nor anywhere else. But there must be a framework which gives Syrian Kurds the same rights as Kurds have acquired in Iraq. We are helping them to develop an orderly and unique political discourse, without imposing solutions. Where the reunification of Syrian Kurdistan with the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq is concerned, it is not on our current agenda. But in the future, who knows? It is the right of every nation to want to be reunited. A natural right, that can only be claimed through peacefull ways and dialogue.

Are you training Syrian Kurd fighters?

There are between 10,000 and 15,000 Kurdish refugees from Syria in Kurdistan. Many of them are young men. It is true that some of them have received training. They have not been trained for attack, but for defence. The regions where they live have no system of defence, and they need to be able to preserve them from chaos.

On 2 August, the head of the Turkish diplomatic service, Ahmet Davutoglu, visited Iraqi Kurdistan. How do you reconcile your solidarity with the Kurds living in Turkey and your growing cooperation with Ankara? What is your position regarding the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is carrying on a guerrilla war on your neighbour’s territory.

We have never wanted the situation in our relation with Turkey to deteriorate. Unfortunately, Turkish policy towards us has been previously bordering on provocation and denial for years. Intimidation, bellicose acts. We do not accept such language, whatever quarter it comes from. It was not our policy, but theirs. But there has been a spectacular turn-around in the Turkish approach. When the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Erdogan went to Diyarbakir and stated that it was true that Turkey had a problem with the Kurds of this country but that there must be a peaceful solution to the “Kurdish problem”, for me this was a move in the right direction. In March 2011, the Prime Minister came to Erbil and declared that the days when Kurds were denied their rights were over. From an economic point of view, our relations have really taken off, and we now have the opportunity to further develop this cooperation.

Where the situation in Turkey is concerned, we uphold the rights of Kurds in that country. But we believe that the change in Turkish policy can be used to achieve further progress in the recognition of these rights. The PKK’s strategy of armed combat is no longer necessary. We neither accept nor support it. We are against this war and this violence. There is now an opportunity for the Kurdish members of the Turkish Parliament to make their influence felt. The opposition can be transformed into peaceful demonstrations in city streets, the Parliament and elsewhere. There is no need for violence. We have told the Kurdish political leaders that they should resolve the problem by peaceful means.

What is your position on the continuation of Iran’s nuclear programme?

Iran is an important player in the region. We share a vast border. We maintain normal relations with Iran. But that does not necessarily mean we agree with everything they do. Where their nuclear programme is concerned, we would prefer it if there was no programme, neither in Iran nor elsewhere. We do not know exactly what their programme consists in. Moreover, we do not know how capable they are of controlling such a programme and, since Chernobyl, everyone knows how the smallest technical problem can lead to a regional catastrophe. We also know, like everyone else, that a programme of this kind may well trigger a war.

You visited the White House last April. What did you and President Obama discuss?

I met President Obama and Vice-President Biden. The main purpose of the meeting was to discuss the situation in Iraq and Kurdistan, and our relations with the USA. It was important for us to know their view of the situation, whether they supported us, and what their position was vis-à-vis particular politicians. They confirmed that they supported the whole political process in Iraq, and the application of the constitution. They confirmed their commitment to the development of an autonomous Kurdistan. Naturally, we raised the issue of our dispute with Prime Minister al-Maliki concerning the problems associated with Kirkuk. President Obama reaffirmed that he wanted us to find a solution in the framework of Article 140 of the Constitution, and he wanted a relaxation of tension between the parties. He was seeking détente. We reaffirmed that we had done nothing that was not in conformity with the Constitution and that our dispute was not about this point. As you know, President Obama has already sent an emissary (Tony Blinken, National Security adviser to US vice-President Joe Biden – ed.) to progress this dossier. But the solution can only be an “Iraqi-style” one.

Where the problem of Kirkuk is concerned, there is no way anyone can impose a solution, neither we ourselves nor anyone else. Article 140 is very clear on this point. To break this rule would be to open the way to other eventualities. All options would then be on the table.

What of your relationship with President François Hollande?

As you know, President François Mitterrand and his wife Danielle gave us loyal support, in particular when the UN established the exclusion zone in 1991 (Resolution no. 688). Relations between our two countries were extraordinarily positive at that time. We had no direct relations with President Chirac, though we were in touch with some of his ministers, such as the Minister of the Interior at the time, Nicolas Sarkozy. With President Hollande, whom I met four or five times when he was leader of the Socialist Party, I have excellent personal relations. I would like to visit France, which for us is one of the countries to which we pay most attention. We would like to deepen our relations. In 2010, I met President Sarkozy in France, in the company of my very good friend, Bernard Kouchner. For me, it was a very warm relationship.

How do you view Russian foreign policy in the region and the blocking tactics Russia, together with China, have adopted in the UN Security Council with regard to Syria?

Historically, there has always been an understanding between Russia and China on certain matters, in opposition to the Western counties. These are very different schools of diplomatic thinking, and there is a struggle for international influence between them. I cannot say which school is right and which is wrong. But, as we see it, the people living in our region may become victims of this struggle.

Is the law you have passed to encourage foreign investment and the establishment of large companies the same as the law adopted in Baghdad?

Our law on foreign investment is very significant in this respect, extremely favourable to foreign investors. Many large multinational companies are interested in the advantages we offer. Some have already taken the plunge and others will soon follow, because we are experiencing remarkable economic development. Our law is different from the law adopted in Baghdad.

How far would you be prepared to go if the central government in Iraq fails to respect the constitutional arrangements agreed between the autonomous region of Kurdistan and the central authorities?

If we found that the constitution was being violated, or emptied of meaning, or not applied, we would not be able to live under such a system. We cannot live under a dictatorial regime in Iraq!

These have been the years of “Arab springs” in the region. But, following these events, we have seen the rise of Salafist and Islamist groups, which have destabilised these countries. Knowing that the American presence in Iraq will not last for ever, what sort of army do you envisage in the future for Kurdistan to defend the country against terrorist groups or external threats?

Our philosophy and strategic doctrine are based on the concept of defence. We will never attack anyone. Never. According to the Iraqi constitution, we are entitled to have our own army to defend us. We have trained our peshmergas to become the basis of this new defence force. They are ready for any future eventuality.

If you were to make a wish for the future of Kurdistan, what would it be? Autonomy? prosperity? independence?

All three (laughter).

BY DIMITRI FRIEDMAN and PIERRE LE BELLER