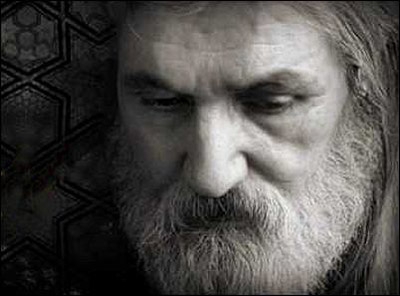

Tribute to Abbas Kamandi: Visionary Singer, Writer, Poet and Painter

Abbas Kamandi, the prominent and prolific Kurdish singer and songwriter, passed away at his hometown of Sina (Sanandaj) earlier this month, leaving behind a rich legacy of original Kurdish art and traditions which he took great pains and pleasure to produce and promote.

Most Kurds remember Kamandi more than anything else as a folk singer with an angelic and nostalgic voice. But he was also a screenwriter, novelist, painter and historian of folk art.

His origins were humble, his childhood immersed in Kurdish culture and music from his father’s side. His grandfather played the Kurdish oboe, or shamshal. The young Kamandi spent his childhood in villages and the city, with Sina his preferred place to live his entire life.

“Sanandaj is my birthplace,” he remarked in an interview. “I come and go as I wish; I do not have to speak another tongue; my father, grandfather and my mother lived in this space; this space is permeated with their breaths and it can feed me and quench my thirst. I feel at home… ”

At 17, his promising genius was discovered when he won first prize for a fictional love story, Shabou and Hamma Shouane (“Shabou and Hamma the Shepherd”), which earned him a job at Radio Sanandaj. There, he met the great folk master and teacher of Kurdish folk music, Hassan Kamkar, father of the world famous Kamkars.

It was here that, after two years, he began to sing. Soon, Kamkar and others saw that the young man was overflowing with literary, musical and intellectual energy. He did not receive a higher education, nor would he have been able to find what had captured his heart and mind: Kurdish folklore, folk music and culture.

No Kurdish composer and singer has, arguably, dominated the field of music from the 1970s to the late 1990s, and until now, as Kamandi has. His work has strongly influenced major Kurdish musicians and composers, such as Kamkars, Andalibi and new singers like Adel Hawrami.

His earliest works (Sabri, a duet with Shahin Talabani, Gol Forosh and Goli Baneh) revealed his musical talent before his joint work with Kamkars’ ensemble in the musical composition and production of Hawraman, pershang, and glavizh, which popularized his works.

Kamandi soon came to be generally admired as a composer and singer of gentle soulful and lovely songs.

During two decades at Radio Sanandaj, Kamandi wrote over 150 lyrics, mostly his own, drawing others from the rich repertoire of Hawraman poets. Some of these tunes topped record sales. It is ironic and unfortunate that, while many of these works were very lucrative, for the most part Kamandi was experiencing financial hardships.

The Islamic Revolution could not silence his inspiring poetic and musical creation, as he always found ways to work his way around prohibitions and anti-music hysteria. His unique approach was to study music and any other folk arts in its cultural context as an ethnomusicologist and indigenous cultural anthropologist.

As noted by one of the Kamkar brothers: “He would study every region’s music. He was indeed an expert on Kurdish music.”

His global and dynamic approach is reflected in the versatility with which he composed and performed in different genres. He would draw inspirations from familiar people, places and events. In an interview with Raman magazine, he recalled running into a Kurdish construction worker in Tehran who in search of a job had left his fiancée. The worker’s nostalgia and longing to be with his sweetheart became the theme of the now famous Keji La De.

In his musical compositions he defied imitative and musical borrowings, advocating original and fresh perspectives. When asked if he had been influenced by Persian music, he remarked: “No. I have influenced Persian music.”

In response to a question about those who “Turkify” their music and present it as Kurdish, he eschewed their work as “king of thieves,” thieves that have stolen from other thieves, as Turks essentially had borrowed their musical tradition from Arabs.

He was also very critical of those who sell Kurdish melodies and tunes to be turned into Persian. He found such acts as “a crime.” He contended that, “the original work would be lost and one day no one can distinguish the original language of the song.”

Kamandi spent 18 years of his life researching, compiling and recording ancient Kurdish folk stories, legends, beliefs, proverbs, puzzles, verbal arts and oral traditions. In addition, he had also collected an anthology of prominent Kurdish notables in Kurdistan and the Kermanshah regions, covering a span of 100 years.

His expanding creativity also included his collection of poems of prominent poets and oral performers like Mirza Shafiq Pawai, whose works have been passed on orally from generation to generation. In doing so, he restored the power of Kurdish language to recapture the world as seen by the poets of the oral traditions.

In his scrutiny of Kurdish oral and written literature, he demystified some fallacies about Mastura Ardalan, who is erroneously known as a poet rather than a great Kurdish female historian. Beyond reviving old traditions, Kamandi also published a number of film scripts, collections of poems, a book volume about Hawraman, another about ancient sports in Kurdistan, a biography of the legendary singer Ali Asghar Kordestani, another title The Alleys of Sanandaj, and many works that remain to be published. Without much notice and without any support, Kamandi also wrote four novels and over 30 scenarios for short and feature-length films during his fruitful years.

Despite the indignities he suffered, his immense capability for love enabled him to capture new heights and psycho-cultural harmony between man, animal and nature. As he had repeatedly noted: “Love is born with us. It is impossible for a human being not to love, and the one who is in love is the most fortunate; love poses many impediments and misfortunes, but makes one creative; art is the work of those in love; if one’s work is not the labor of love, it will have nothing to do with art.”

His vivid and expressive vision would lift him from poetic imagination to romantic images of Kurdish landscape that invade his paintings: Snow-covered mountains; lucid rivers; a white crane drinking water from a stream; lovers sitting on a patch of snow under a snow-covered tree near their snow-covered village.

Kamandi rarely performed in concerts. He valued his work as a cultural frame, deeply embedded in Kurdish cultural community and historical contexts. Despite long periods of dismay, dehumanizing treatment and exploitation of his work by both institutions and abusive entities and individuals who cashed in on his works, Kamandi remained truthful and uncompromising when it came to the integrity of his works. His penetrating repertoire of genius has yet to be appreciated by Kurds everywhere.

In 2011, the Mamleh Arts Foundation in the Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq awarded him its annual prize. An exhibition of his paintings was held in 2012 in Sulaimani, to which he was invited a second time to sign one of his publications.

Although for most Kurds Kamandi remains a legendary singer of love songs and a testament to the living power of Kurdish music, we have yet to discover his multi-dimensionality as a painter, researcher, poet, script writer, novelist and art historian. His visionary work has given young Kurdish artists fresh perspectives and new respect for their rich culture, which many of them take for granted. His very life, indeed, was the ideal specimen of Kurdish folkloric being, thinking, and feeling.

On May 22, 2014, in a final farewell, thousands of his mourning hometown residents, friends, fans, as well as many artists, musicians, writers and poets, accompanied him to his eternal resting place in his beloved Sanandaj, some with the Kurdish traditional funeral procession of playing daf, or frame drum.

Rudaw