Kurdish Ambitions Test Turkey's Uneasy Peace With U.S.

As night falls in Akcakale, Turkish armored vehicles rumble into position behind walls of protective sandbags, diverting their guns from a town across the Syrian border controlled by U.S.-backed Kurdish fighters. The dust-churning maneuver ends another day of a tense truce between NATO’s second-largest army and a militia it considers a mortal enemy.

The adversaries are separated only by untended fields of cotton, barbed wire and tracks of the Berlin to Baghdad railway that was conceived more than a century ago to further imperial claims on territory.

Fighting in Akcakale in 2016.Photographer: STR/AFP via Getty Images

Turkey says its military is confronting another attempt to redraw the region’s maps. It believes Syrian Kurds have been joined by their armed Turkish brethren to better pursue a long dreamed of Kurdish state that Ankara will not countenance. The standoff at the frontier could easily explode.

In his latest saber-rattling intervention, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said on Tuesday that Turkey can’t stand by while it’s menaced by the Kurds. The “days when we will crush terrorists are very near,” he said. The president then chaired a five-hour meeting of the National Security Council.

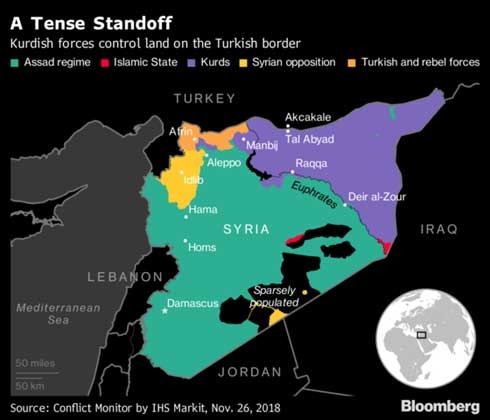

A Tense Standoff

Kurdish forces control land on the Turkish border

Erdogan has sent troops into northern Syria to attack Kurdish positions before and is especially angered by a decision the U.S. says was intended to help keep the peace.

Last week, Defense Secretary James Mattis outlined plans to set up observation posts to warn Turkey of any dangers heading its way, perhaps redeploying some of the American troops who have been assisting the Kurdish YPG in the fight against Islamic State. Turkish leaders, however, see the plan as really designed to protect the Kurds by putting Americans in harm’s way of an attack by Turkey.

Why Kurdish Statehood Dream is Turkey’s Nightmare: QuickTake

Erdogan has been ramping up his nationalist rhetoric ahead of municipal elections in March, but that doesn’t mean his threats are idle or that there’s little at stake.

U.S. officials have warned that extending Turkish military action east along the Syrian frontier would raise the chances of a direct confrontation with American troops. It would also damage international efforts to prevent a jihadist resurgence by drawing Kurds from a battle they fought for years to win, they say. Erdogan rejects those claims as propaganda.

The YPG, or People’s Protection Units, are affiliated with the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party. Both deny they are enemies of Turkey and say they seek only to protect Syria’s Kurds. They have controlled swaths of northern Syria since 2012, when the government in Damascus withdrew troops to bolster its heartlands. The militia temporarily lost some key towns to Islamic State’s brutal advance before retaking them backed by U.S. air power.

Turkish Sights

Its sporadically hot border conflict with Turkey since then has made household names of a string of formerly obscure frontier towns. There’s Afrin, seized from the Kurds by Turkey in March, and Manbij, which Erdogan has repeatedly vowed to take. From Akcakale, it’s Tal Abyad that’s in Turkish sights.

Turkey has been preparing to capture the town using allied Syrian Arab forces, according to two people familiar with the planning who asked not to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue.

An offensive would likely open new rifts between Ankara and Washington only weeks after a crisis over a jailed American pastor was resolved. Mattis nodded to those better relations in the Nov. 21 Pentagon briefing where he outlined the observer mission.

Sharing a border with Syria gives Turkey plenty of reasons to be concerned and “we don’t dismiss any of their concerns,” he said. “We are going to track any threat that we can spot going up into Turkey. That means we will be talking to Turkish military across the border.”

Turkish Doubts

At the moment, Turkey isn’t buying it. Defense Minister Hulusi Akar said he’d told U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford at a security forum in Canada last week that the U.S. plan would “negatively affect the perception in our country that American soldiers were protecting the YPG.”

Hundreds of refugee Syrians including tribal leaders have demonstrated in Akcakale to demand an operation against Tal Abyad.

Their mood chimes with that of Erdogan and his nationalist political allies, who in election campaigning claim the YPG is now virtually indistinguishable from Turkey’s Kurdish PKK separatist movement.

Turkey says that commanders of the PKK, which has battled the Turkish state for autonomy for much of its 40-year history, have taken over the YPG. The PKK is designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. and European Union.

‘Killing One Another’

Nihat Ali Ozcan, an analyst at the Ankara-based Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey and author of several books on the PKK, said the group moved to aid their “ethnic cousins in Syria against Islamic State and quickly took over the command of the YPG.”

Other analysts are more circumspect but point to links. In a 2016 Atlantic Council study, Aaron Stein said Turkish officials at first looked the other way as Kurds left to join the YPG and fight Islamic State “given that two entities hostile to Turkey were killing one another.” That has since changed but YPG statements show Turkish Kurds accounted for nearly half of casualties over three years from January 2013, he said.

Top Turkish policymakers are urging the U.S. to change course in Syria. Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said last week that Washington must force the Kurds to fully withdraw from Manbij, a predominantly Arab town, by the end of the year and make sure the YPG has no presence west of the Euphrates River. Turkish and U.S. army units started joint patrols near Manbij on Nov. 1, but Turkey isn’t satisfied. Turkey might move against Manbij early next year should Kurdish forces fail to withdraw to the east of the river, according to two officials who spoke on condition of anonymity due to sensitivity of the information.

Russia, Assad’s main backer, and Turkey struck a deal in September to prevent a government offensive on Idlib that threatened to trigger a fresh wave of refugees. With Turkey under pressure from Moscow to deliver on its promise to remove Islamists from a demilitarized zone around Idlib, its scope for a new northern offensive may be limited.

That hasn’t dampened speculation in Akcakale. “There are rumors that authorities will evacuate us from our houses just near the border,” said Hasan, who refused to give his surname fearing reprisals. “There is calm now but we’re worried.”.

— With assistance by Samuel Dodge