Kurds can pull off miracles, but they need help against Isis

The Kurds can pull off minor miracles when they need to. They require active support, however, now they are at the centre of the global struggle against the self-styled Islamic caliphate, Isis. Recent history shows the Kurdish potential.

Eight years ago in Iraqi Kurdistan, there was much talk about oil and gas reserves. Some thought it was all hot air; their oil sector is now huge and has driven another once impossible dream – rapprochement with Turkey, which needs vast energy supplies to fuel its growing economy. Energy could even fuel Kurdish independence.

However, a longer history hangs over the Kurds. Nearly a century ago, Kurdish hopes of a single nation-state were snuffed out. Some say they weren’t ready, others say they were betrayed. Four Kurdistans have since emerged in Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, each repressed to some degree.

That century has deepened Kurdish differences. A bewildering alphabet soup of abbreviations describes the ‘virtual Kurdistan’ – PYD, YPG, YPJ, KNC, PKK, KDP, PUK, KRG, KDPI – the main military and political actors in Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Iran.

A century of separation has spawned a variable geometry of democratic development, with the new democracy of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region furthest ahead but still a work in progress.

Furthermore, the Kurds are surrounded by powerful neighbours who usually seek to divide them. One neighbour, Turkey is in the doghouse among Kurds because it says the fighters of the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) are equivalent to Isis, and initially refused to allow Kurdish fighters and weapons through its border with Syria to the besieged town of Kobani. Turkish forces arrested and teargassed Kurds on the border where its tanks sat, while Isis pounded Kobani.

Turkey has also not allowed jets from fellow Nato members to use its Incirlik air base, although this would mean they could more easily and cheaply strike Isis in Syria. The Kurdistan Region’s capital, Erbil, came close to being overrun or heavily damaged by Isis in early August, but Turkey seemed silent. It had no obligation to help under its 50-year economic relationship with the Kurdistan Region or as its main trading partner, but some argue that it had a moral duty. They point out that Iran, the region’s second biggest trading partner, rushed arms within a day – in its own interests of stopping Isis – and although it had no obligation.

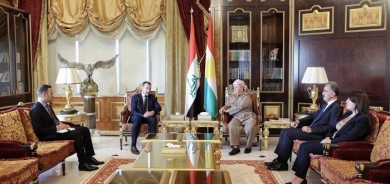

Turkey may have been discreet in its support at the time, because nearly 50 diplomatic hostages were in Isis hands and it was in the middle of a presidential election where emotions about the Kurds were running high. Furthermore, Turkey has since concluded a deal with the Kurdistan Region’s president, Massud Barzani, for peshmerga fighters and heavy weapons to transit from Turkey to Kobani.

Barzani’s diplomacy has also persuaded the main Kurdish military and political force, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), in the three Syrian cantons that constitute what the Kurds call Rojava, that they need to work with other Kurdish forces.

However, relations between the PKK and Turkey are heading toward a freeze, amid fears that their ceasefire will break down. There is Kurdish anger about an attack on PKK fighters in Kurdistan. Turkey is angry about the assassinations of police officers and inaction against Syrian President Assad, who is responsible for up to 300,000 deaths.

This is a delicate moment in which Turkish chickens are coming home to roost, so to speak. Yet there are signs of change in Turkey’s posture; these should be nurtured rather than making Turkey the butt of mainly leftist criticism, which include calls for its suspension from Nato. Attacking Turkey is a displacement exercise for some leftists who, still mesmerised by the intervention in Iraq in 2003, cannot recognise that the West should employ more armed action in support of the Kurds and Iraqis.

Three common sayings in Iraqi Kurdistan define their history: ‘we have no friends but the mountains’, ‘we live in a tough neighbourhood’ and ‘we cannot choose our neighbours but we can choose our friends’. Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria – or what is left of it – will remain neighbours. The priority now should be to forge pragmatic and durable accords to defeat the Isis military machine and undermine the appeal of fundamentalism. Secular Kurds, with greater unity of purpose and greater support from the West, are the key to this.

Gary Kent is the director of the UK’s all-party parliamentary group on the Kurdistan Region. He has visited Iraq 19 times since 2006, and writes in a personal capacity. He tweets at @garykent.

The Spectator