Once a Ghost Town, Halabja Now Home to Arab Refugees

HALABJA, Kurdistan Region—Youssef Ihasan and his family live in a cramped, poorly furnished house in the Kurdish city of Halabja with 24 people.

The three families, who fled violence in other areas of Iraq to this mountainous town near the Iranian border, are grateful for security in Iraqi Kurdistan but live in constant fear that they won’t be able to pay the bills. The rent is 350,000 dinars ($300) and money is tight.

“We came here in the hopes of protecting our families,” he said. “We have no work to support them.”

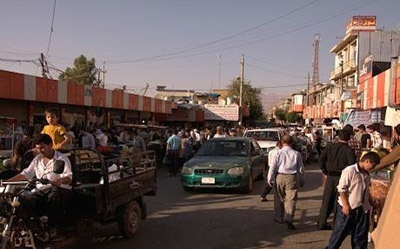

Halabja, some 350 kilometers east of Mosul, lies at the base of a stunning summer resort that attracts thousands of Arab tourists who enjoy the cooler mountain temperatures. But some aren’t here on holiday, and are instead struggling to survive after fleeing violence in central and western Iraq.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) is reporting that 1 million people are now displaced in Iraq, and according to ACTED, an international relief agency, an estimated 500,000 people have fled Iraq's second biggest city, Mosul, after it was seized by Sunni extremists and tribes last month. Of those displaced, an estimated 300,000 fled to the Kurdistan Region.

Unlike other parts of Iraqi Kurdistan, however, there are no camps or services for displaced Iraqis in Halabja.

“No humanitarian or government agency has come to our aid,” said Farhad Abdulhadi, a refugee.

“These displaced families live in poor conditions,” said Hemin Kakabra, a relief worker in the nearby town of Sharazour. “They stay in houses that are poorly furnished and have limited access to drinking water and electricity.”

Kakabra said aid workers have told the United Nations that refugees need more aid.

The influx of refugees is pushing up the cost of housing and jobs are in short supply for Arabs in Halabja, where in addition to Kurdish residents are more likely to speak Farsi than Arabic. The economy has also contracted since the Iraqi government cut funds to Iraqi Kurdistan in January.

In the city’s bazaar, laborers including Arabs and Iranians wait to be picked up for construction work and other odd jobs.

Wasta Mohammed, 62, runs a small carpentry shop nearby. Mohammed is a fluent Arabic speaker — a rarity in this town, which is nestled along the rugged Iranian border — having learned the language as a bus driver in Baghdad 40 years ago and as a political prisoner under Saddam Hussein’s regime in the 1990s.

Like many Kurds, he can relate to the stories of displaced Arabs. The Iraqi military bombed Halabja with chemical weapons in 1988, killing an estimated 5,000 people and forcing tens of thousands to flee to Iran.

In his shop, Mohammed said he listens to stories from refugees. One young man from Falluja, which has been a center of fighting between Sunni militias and the Iraqi government for months, is responsible for 11 family members but can’t find work. Another, a cleaner at a mosque, fled to Halabja from Baghdad four years ago after the imam at their mosque was burnt alive.

There are currently no camps in Halabja for the refugees. Instead they have to rent a house, which requires a Kurdish local sponsor and a security check — a system many locals support for fear that terrorists will try to pass off as refugees. Refugees without sponsors are turned away.

Many of Halabja’s residents lived in refugee camps in the 1980s and 1990s, and say camps need to be erected for refugees to receive shelter and food. Halabja’s local government officials maintain the responsibility lies with the provincial authorities, which haven’t taken action.

Rudaw