Syria conflict: UN reports mass executions by ISIS

The commission of inquiry's latest report documents several incidents blamed on the al-Qaeda-linked Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS).

Government forces are meanwhile accused of sharply increasing their use of indiscriminate weapons, such as barrel-bombs, against civilians.

The report was released before a debate at the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

In a separate development, the US state department told the Syrian government that it must immediately suspend its diplomatic and consular missions in the US and withdraw all personnel who were not US residents.

The newly appointed US special envoy, Daniel Rubenstein, said the order was a response to the Syrian embassy's decision to suspend consular services, as well as the "atrocities the Assad regime has committed".

'Execution field'

The report by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria covers what it says were the "most egregious violations" of human rights committed between 20 January and 10 March.

At the start of January, deadly clashes erupted when Western-backed and Islamist rebel groups launched co-ordinated attacks on ISIS strongholds in northern and north-eastern provinces of Syria.

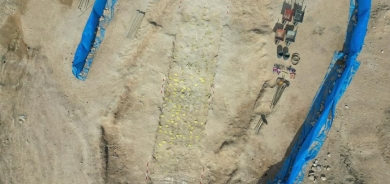

In the days and hours before their bases were overrun, ISIS fighters "conducted mass executions of detainees, thereby perpetrating war crimes", the UN report says. The number killed as well as allegations of mass graves connected to these executions remain under investigation.

The report says that on 6 January at Aleppo's children's hospital, which was used by ISIS as its headquarters, a guard began summoning certain detainees out of their cells, after which they were taken outside and killed in what was described as an "execution field" nearby.

Several other examples of mass executions of detainees are listed.

'Area bombardment'

In addition, the UN investigators found that after 20 January the government had ramped up its campaign of dropping barrel-bombs - explosive-filled cylinders or oil barrels - onto densely-populated residential districts of Aleppo, with devastating consequences.

The unceasing bombardment - at the same time as representatives of the government were attending peace talks with the opposition in Geneva - caused extensive civilian casualties and led to the large-scale displacement of people from targeted areas, the report says.

"Civilians have been killed from the initial blasts and the shrapnel that results. Others have been killed in the collapse of buildings around the impact site. Bodies were torn apart by shrapnel and flying debris. Survivors commonly spoke about seeing bodies without limbs or heads."

The report says that barrel bombs cannot be precisely targeted and their use is therefore indiscriminate. Furthermore, it adds, in many incidents there was no clear military target in the proximity of the area attacked.

"The use of barrel bombs in this context amounts to 'area bombardment', prohibited under international humanitarian law. Such bombardments spread terror among the civilian population."

The report says denial of food, water, electricity and medical help are all commonplace in Syria now, and that people are starving to death in besieged towns and in detention centres.

The chairman of the commission of inquiry, the Brazilian diplomat and legal scholar Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, said it had identified those suspected of committing war crimes and added their names to a list.

The suspects include the heads of the various Syrian intelligence agencies, those in charge of detention facilities where torture occurs, military commanders who target civilians, officials overseeing airports where barrel-bomb attacks are planned and executed, and the leaders of rebel groups and pro-government militia involved in attacking civilians.

The BBC's Imogen Foulkes in Geneva says prosecuting those guilty of war crimes would need a referral to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Only the UN Security Council can do that, our correspondent adds, and it remains deeply divided over Syria.

One UN investigator, former war crimes prosecutor Carla Del Ponte, suggested an ad-hoc tribunal instead. She would take the case herself, she said, because the evidence was so extensive and so compelling.

BBC