Ukraine protesters seize Yanukovich's compound in Kiev

Protesters seized the Kiev office of President Viktor Yanukovich on Saturday and his whereabouts were a mystery, as the pro-Russian leader's grip on power rapidly eroded following bloodshed in the Ukrainian capital.

At the president's headquarters, Ostap Kryvdyk, who described himself as a protest commander, said some protesters had entered the offices but there was no looting. "We will guard the building until the next president comes," he told Reuters. "Yanukovich will never be back."

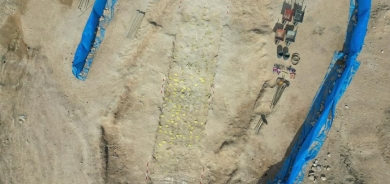

The grounds of the president's residence outside Kiev were also being guarded by "self-defense" militia of anti-government protesters. Hundreds of people entered the grounds, although not the building itself.

A senior security source said the president was still in Ukraine but was unable to say whether he was in Kiev. An ally was quoted as saying he was in an eastern city.

Yanukovich, who enraged much of the population by turning away from the European Union to build closer ties with Russia three months ago, made sweeping concessions in a deal brokered by European diplomats on Friday after days of violence that killed 77 people, with central Kiev resembling a war zone.

But the deal, which called for early elections by the end of the year, was not enough to satisfy demonstrators, who want Yanukovich out immediately, following bloodshed in which his police snipers were shooting from rooftops.

Parliament has quickly acted to implement the deal, voting to restore a constitution that curbs the president's powers and to change the legal code to allow his arch-adversary, jailed opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko, to go free. On Saturday lawmakers voted to speed her release without requiring the president's signature.

The speaker of parliament, a Yanukovich loyalist, resigned on Saturday and parliament elected Oleksander Turchynov, a close ally of Tymoshenko, as his replacement.

Events were moving at a rapid pace that could see a decisive shift in the future of a country of 46 million people away from Moscow's orbit and closer to the West, although Ukraine is near bankruptcy and depends on promised Russian aid to pay its bills.

"Today he (Yanukovich) left the capital," opposition leader Vitaly Klitschko, a retired world heavyweight boxing champion, told an emergency session of parliament debating an opposition motion calling on the president to resign.

"Millions of Ukrainians see only one choice - early presidential and parliamentary elections." Klitschko then tweeted that an election should be held no later than May 25.

The senior security source said of Yanukovich: "Everything's ok with him ... He is in Ukraine." Asked whether the leader was in Kiev, the source replied: "I cannot say."

The UNIAN news agency cited Anna Herman, a lawmaker close to Yanukovich, as saying the president was in the northeastern city of Kharkiv, in a mainly Russian-speaking province.

Two protesters in helmets stood at the entrance to the president's Kiev office. Asked where the state security guards were, one, who gave his name as Mykola Voloshin, said: "I'm the guard now."

Dmytro Pylipets, 32, a doctor from Kharkiv in military fatigues and helmet, said: "I think Yanukovich is frightened and panicking. I feel we are almost there. The Maidan revolution is almost done."

In a sign of the quick transformation, the interior ministry responsible for the police appeared to swing behind the protests. It said it served "exclusively the Ukrainian people and fully shares their strong desire for speedy change".

Parliament voted on Friday to dismiss Interior Minister Vitaly Zakharchenko, a Yanukovich loyalist blamed by the opposition for the bloodshed.

The ministry urged citizens to unite "in the creation of a truly independent, democratic and just European country".

Yanukovich's broad concessions on Friday ended to 48 hours of violence that had turned the centre of Kiev into an inferno of blazing barricades. Without enough loyal police to restore order, the authorities had resorted to placing snipers on rooftops who shot demonstrators in the head and neck.

The foreign ministers of France, Germany and Poland negotiated the concessions from Yanukovich, in what the Kremlin's envoy acknowledged as superior diplomacy.

"The EU representatives were in their own way trying to be useful, they started the talks," said Russian envoy Vladimir Lukin. "We joined the talks later, which wasn't very right. One should have agreed on the format of the talks right from the start," Lukin was quoted as saying by Interfax news agency.

Yanukovich, 63, a burly former Soviet regional transport official with two convictions for assault, did not smile during a signing ceremony at the presidential headquarters on Friday.

"YOU'LL ALL BE DEAD"

It took hard lobbying to persuade the opposition to accept the deal, and crowds in the streets made clear they were not satisfied with an arrangement that would leave Yanukovich in power. Video filmed outside a meeting room during Friday's talks showed Polish Foreign Minister Vladislaw Sikorski pleading with opposition delegates: "If you don't support this, you'll have martial law, you'll have the army, you'll all be dead."

Anti-government protesters remained encamped in Independence Square, known as the Maidan or "Euro-Maidan", through the night. They held aloft coffins of slain comrades and denounced opposition leaders for shaking Yanukovich's hand.

The week's violence was by far the worst to hit Ukraine since it emerged from the breakup of the Soviet Union.

With borders drawn up by Bolshevik commissars, Ukraine has faced an identity crisis since independence. It fuses territory that has been integral to Russia since the Middle Ages with provinces that were parts of Poland and Austria until they were forcibly annexed by the Soviets in the 20th century.

In the country's east, most people speak Russian. In the west, most speak Ukrainian and many despise Moscow. Successive governments have sought closer relations with the European Union but have been unable to wean their heavy Soviet-era industry off dependence on cheap Russian gas.

The past week brought the country to the verge of splitting, with central authority vanishing altogether in the west, where anti-Russian demonstrators seized government buildings and police fled. Deaths in the capital cost Yanukovich support of wealthy industrialists who previously backed him.

Yanukovich's fall would be a setback for Russian President Vladimir Putin, who had made tying Ukraine into a Moscow-led Eurasian Union a cornerstone of his efforts to reunite as much as possible of the former Soviet Union. Putin had offered Yanukovich $15 billion in aid after Yanukovich spurned an EU trade pact in November for closer ties with Moscow.

Moscow has maintained that the protesters were terrorists and coup plotters, denounced the West for supporting them and encouraged Yanukovich to crush them.

"This is not democracy, this is anarchy and chaos. And we'll see what comes out of it," Alexei Pushkov, head of Russia's State Duma foreign affairs committee and a member of Putin's United Russia party said after the deal was signed, though he said the pact would be positive if it ended violence.

Washington, which shares Europe's aim of luring Ukraine towards the West, took a back seat in the final phase of negotiations, its absence noteworthy after a senior U.S. official was recorded using an expletive to disparage EU diplomacy on an unsecured telephone line last month.

U.S. President Barack Obama spoke to Putin by phone. The White House said they agreed to help ensure the deal works.

The outlook for Ukraine's economy is dire and Russia has not made clear whether it will still pay the promised $15 billion in aid. Ukraine cancelled a planned issue of Eurobonds worth $2 billion on Thursday. Kiev had hoped Russia would buy the bonds.

(Additional reporting by Matt Robinson and Richard Balmforth; Writing by Peter Graff; Editing by Mark Heinrich and Alistair Lyon)

(Reuters) -