‘Nightingale of Iran’ Receives Attacks and Support for Kurdish Song

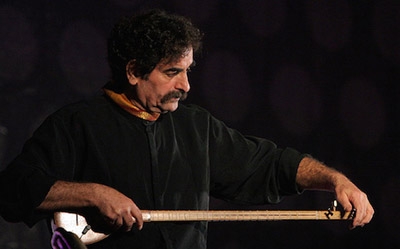

COPENHAGEN, Denmark - "Shahram Nazeri is the nightingale of Iran," The New York Times once wrote about the renowned icon of Kurdish and Persian classical music, named Best Singer of Sufi Music by Iran’s ministry of culture.

But the famous singer stirred up controversy in Iran last month, when he sang a popular Kurdish song in his native Kermanshah. The song, “Xom Kermashanai, Farsi Niyezanim,” means “I am from Kermanshah, I don’t know Farsi.”

That provoked Iranian media attacks against Nazeri, with accusations that his song was an attack on national feelings and advocated separatism and Kurdish nationalism against the Persians.

After a few days, the severely criticized singer broke his silence and defended himself by saying the song is not at all political.

"The song is based on an old poem, entirely devoted to love. But someone wants to create conflicts and make a big issue out of this," he said in media comments.

The singer explained that he does not discriminate against anyone with his art. "But as my whole basis is the Kurdish culture, it is only natural that I attach importance to the Kurdish language," he added.

A Facebook campaign, under the slogan “Kermanshah is Kurdistan and the Kurdish language is our identity,” has risen up in support of Nazeri. In a short time the page has received more than 12,000 likes. In solidarity with the singer, some people have posted pictures of themselves holding signs echoing the words of Nazeri’s song: "I am from Kermanshah and don’t know Farsi."

"As an active, political and Kurdish group, we condemn in the strongest terms the Iranian media discrimination and defend our culture, history and nation," campaign officials said.

The Kurds are one of the largest minorities in Iran, with an estimated eight million population, but no legal political party in the country. Kurdish education in public schools is not allowed. The Kurds have often been in conflict with the government in Tehran on the right to self-government and cultural and linguistic rights.

According to Barzoo Eliassi, researcher at Oxford University and an expert on Kurds in Iran, Persian identity has dominated the country’s minority languages and groups.

“Nazeri's song was thus seen as a direct attack on the dominance of Persian identity and language in Iran,” he told Rudaw.

“Although Kurdistan exists as an official province in Iran, the Iranian media did not expect a song perceived as an anti-national song from a non-political person like Nazeri,” Eliassi added.

“Many Kurdish singers used to sing nationalist songs about Kurdistan, but the difference is that Nazeri performed a song in the heart of Kermanshah that asserts Kermanshah as a Kurdish-speaking town,” Eliassi explained.

Hejar Dashti, an expert on Kurds at Copenhagen University, said the backlash against Nazeri is unlikely to lead to serious problems for him, such as being forced to leave Iran.

“It's a reaction from a nationalistic group in Iran, which makes a big issue out of this. But it doesn't look like they will succeed in their project, because people don’t want to expend energy on such issues when the country is facing many other problems,” he said.

Rudaw