From Kurdistan to New York

July 18, 2013

From Media

I’ve just spent several days travelling around Iraqi Kurdistan, a region that endured the worst of Saddam Hussein’s furies in the nineteen-seventies and eighties. Suleimaniya, the Kurdish city where I was staying, is a boom town; cranes and high-rises clutter the horizon; the roads, many of them smooth and new, are crammed with cars. Women walk the streets in jeans, their hair blowing free. Kurdistan, a self-governing region, has a decadelong head start on the rest of Iraq, and it has peace, too. For that, it can thank—and Kurds do thank—the United States, and especially for the no-fly zone, erected in 1991, that kept Saddam’s armies at bay, until the U.S. took him and his government down, twelve years later. The Kurds are reaping the fruits.

What struck me as most remarkable in my travels around the region, though, was that, for all the economic growth of the past few years, the Kurds have not given up their old ways—not entirely, not yet. For now, the traditional and the frantically modern exist together in a kind of nervous balance. In the West, much has been written about the bizarre sensation of travelling to an impoverished land, or being stuck in a city hit by disaster, where, stripped of the Internet and the smartphone, people suddenly feel their attention spans coming back to them. They begin to listen to their friends again, to speak to their children. This Web site recently wrote about a kind of day camp where people pay money to leave their gadgets behind and tramp around in the woods.

Technologically and economically speaking, Kurdistan is thoroughly modern now. People carry smartphones. Cafés and hotels offer WiFi (and, remarkable for the Middle East, there is no Internet censorship). The electricity flows continuously. You can buy beer at 4 A.M., which I happily did. The main drag through Suleimaniya boasts a Jaguar dealership. No one in Kurdistan thinks any of this is a big deal.

And yet, for all the technological and economic progress, people are still clinging to many of the things that a modern economy usually tears to shreds: free time, families, friendships. On a recent Friday night, I accompanied my Kurdish friend Warzer Jaff to a private dinner club, called Talar, where his extended family gathered with about a dozen other families for the evening. On the stage, two singers took turns: Kaewan, who sang classical Kurdish songs, and Meran, who sang modern songs. Most of the adults were drinking. On the floor, men and women, elbows locked, formed large semicircles and did the rashbalak, a traditional Kurdish dance. Young and old swayed together with elegant, rhythmic steps. Meanwhile, the children—and there were lots of them—ran among the tables, whispering to each other, shouting, and, most remarkably, disappearing for long stretches. The parents didn’t worry about young children vanishing for half an hour at a time, content in the knowledge that the kids would be looked after by one of their friends in attendance or even by the guard in the parking lot. In Suleimaniya, most people still know each other, or their families do. At the Talar dinner club, there were smartphones present, but they lay on the tables, mostly undisturbed. The families who came that night, Jaff told me, gather every Friday.

Is such a scene even possible in a large American city? A casual family gathering—entire families, teens included, getting together with other entire families—on a Friday night? Undistracted by work, by text messages? Where adult brothers and sisters still live within a few miles of each other? Where they still speak to each other? Maybe I’ve been away from Florida for too long, but in New York an affair of the type I witnessed in Suleimaniya would be miraculous; on a regular basis, impossible. In the long run, in Kurdistan, they are probably doomed. But for now it’s an amazing thing to see, the old ways accepting the new ways, but holding them at arm’s length.

Across town, the Nali Café offers plush sectional couches, thin-crust pizza, and espresso that’s rich and sharp; the WiFi flows as steadily as the air-conditioning—which is a good thing, since the daytime temperatures outside usually hover around 110 degrees. The Nali is a welcoming place to linger and work, and on many days I stayed there for three or four hours. Not once did a waiter flash a phony smile and ask, “Is there anything else before I bring you the check?” The same went for the outdoor restaurant at the Chwar Chra Hotel (it means “four lanterns” in Kurdish), in the nearby city of Erbil. Diners lingered over their kebabs and beer until 2 A.M.

One more thing I noticed in Suleimaniya: the economic boom has brought many Kurdish families their first automobiles. The city, sleepy and quiet ten years ago, is now crammed with cars. The traffic is horrendous. Except on Fridays. That’s the Kurdish day off, and on Fridays the streets of Suleimaniya were all but empty. In the middle of the afternoon, I could have rolled a bowling ball down Salim Street, the city’s main drag. I am almost dreading my return to New York, and the manic pace that awaits.

As it happens, I’ve been carrying around a battered copy of “War and Peace.” About a third of the way through the book, one of the main characters, Prince Andrei, feels a similar predicament. After being wounded in Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, Prince Andrei, at the age of thirty-one, retires to his country estate, where he lives quietly for two years. Then he feels the pull of Petersburg, the lure of the city, and before long he finds himself thrust back into the rapid-fire pace of urban life. Here is what he feels:

During the first weeks of his stay in Petersburg Prince Andrei found all the habits of thought he had formed while living in seclusion entirely eclipsed by the petty preoccupations that engrossed him in that city.

On returning home in the evening he would jot down in his memorandum book four or five unavoidable visits or appointments for specified hours. The mechanics of life, the arrangement of the day so as to be on time everywhere, absorbed the greater part of his vital energy. He did nothing, did not even think or find time to think, and only talked, and talked well, of what he had had time to think about in the country.

He sometimes noticed with dissatisfaction that he repeated the same remark on the same day in different circles. But he was so busy for whole days together that he had no time to think about the fact that he was doing nothing.

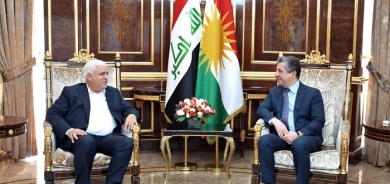

Photograph by Donald Weber/VII.