Where Were You When You Heard About Halabja?

LONDON – Where were you when you heard about Saddam Hussein’s poison-gas attack on the Kurdish town of Halabja, 26 years ago this month?

Except for those directly or indirectly affected by the March 16, 1988 attack, in which 5,000 Kurdish villagers were gassed to death, the atrocity did not make a very large impact on most people.

In a world without social media -- and without much international interest in what was happening to the Kurds as long as Saddam was confronting Ayatollah Khomeini’s Iran -- there was no outcry against the Iraqi dictator’s heinous crime.

In addition, difficult communications, censorship and even a refusal to believe the facts conspired to make news of the attack slow to emerge, and for a time open to challenge.

For these reasons, even academics and politicians who have since become ardent advocates of remembering Halabja, told Rudaw they find it difficult to remember exactly when they heard about the attacks.

Mehmet Asutay was studying public finance at the University of Istanbul when the news began to filter out to the world.

“I’m from the Turkish part of Kurdistan and you have to understand the historical circumstances of the time. There was censorship and the news was completely controlled. There was no social media and Halabja was very much not a big thing in Turkey,” says Asutay, now a professor at Durham University in the UK, where he is also director of the Centre for Islamic Economics and Finance.

“Only those people with a personal interest and informal networks could develop any understanding of what really happened. For many other people, it took about a year to understand. The news of Halabja did get through, but not the enormity of what had happened,” he says.

“We were also told that Iran was the culprit, but I knew that couldn’t be true. I was politically active and I knew it was Saddam Hussein. It was clear from the beginning.”

The only positive aspect to Turkish censorship meant that the slow unraveling of the news meant it gave people time to come to terms with what had happened, rather than suffer a big, immediate shock, he says.

He still felt helpless, however. He moved to the UK in 1989 to pursue his post-graduate studies and on the anniversary of Halabja he would organize exhibitions and talks for his fellow students. This was received badly by the Turks among them, he says.

“The concept of deferred justice, of justice in the hereafter for Muslims, bothered me. The idea of deferring justice is not only religious but cultural and widespread in the region,” he says.

He noted that on this year’s Halabja anniversary, several mass-circulation Turkish newspapers did have reports and photographs of mass graves. “This is the first time as far as I’m aware,” he says. “Perhaps the fact that (President Massoud) Barzani is practically the Turkish government’s only friend had something to do with it.”

He hopes for the memory of Halabja to become a unifying factor for all Kurds, to be remembered by all Kurds wherever they live. “I want Halabja remembered not for revenge but for closure and justice. I would like to see events in Diyarbakir, not just in the KRG (Kurdistan Regional Government).”

Alistair Hay, professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Leeds, has worked with victims of Halabja since within weeks of the attack.

“I must have heard about the attack on TV at home,” says Hay, who has been campaigning against chemical weapons since 1980.

He was asked to meet Halabja victims who were flown to the UK, to interview them and to record their injuries and other evidence in order to alert the world.

“I was apprehensive about seeing them and I was outraged as well. I was also desperate to talk to them to find out everything, to use this in some way to argue for a chemical weapons convention and to pressure governments.”

He recalls that, at the time, British ministers made encouraging statements against the attacks. “But as far as the west was concerned, Iran was the bogeyman.”

He used the evidence about Halajba to gain access to the media and did many interviews. “I was able to have a lot of access to condemn the attacks to put pressure on Saddam Hussein for him to be tried in some way for war crimes.

“Halabja really did put fuel in everybody’s tank and pushed negotiations for a chemical weapons convention. (US President) George Bush tabled a discussion, so something came out of this horrendous and awful event.”

The Chemical Weapons Convention came into force in 1997 and has now been signed by some 190 countries.

Nadhim Zahawi, the first and only Kurd to be elected to the British parliament, was 21 when news of the attack emerged from Halabja. “Despite my family having fled from Iraq some 14 years earlier, it was still inconceivable that such a thing could happen, and the international community would let such heinous acts pass with little comment."

His family received some of the first photos that were smuggled out of Halabja. “And my Dad, along with other British Kurds, even paid for a booklet to be made in an effort to show the world the horrors the Kurds faced under Saddam Hussein. But tragically, the media weren’t interested, and the persecution continued."

His family still has those images locked away, their images “no less shocking after 26 years. Yet they serve as an important reminder that if we let human rights abuses go unchecked and ignored, we sow the seeds for future instability, conflict and humanitarian crisis,” he says.

Hamish De Bretton-Gordon, a chemical and biological counter-terrorism expert, was a young soldier at the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst at the time of the Halabja attack.

“As a young soldier, we did chemical-biological defence training and the reason was the attack in Halabja,” he says. “Flip to three years later, and I was driving through the sand of Iraq in a tank (during the 1991 Gulf war),” he says.

“For us as soldiers, the use of chemical weapons felt very real. We used to think it’s never going to happen, but it did.”

He never imagined Halabja and Kurdistan would become a big part of his life. He is a former commander of British chemical and biological counter-terrorism forces who also served in Iraq in the 2003 war.

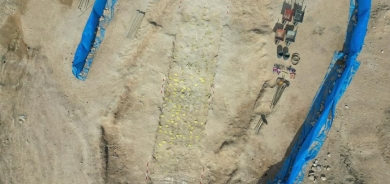

He now runs a company called SecureBio and has visited Halabja around half a dozen times. He was asked by the KRG to study the decontamination of Halajba and says a full clean-up of the province is feasible and would take around two years.

Most recently, he has drawn parallels between the chemical attack there and that on Ghouta in Syria last August.

“The KRG and others have to keep talking about chemical weapons so people realize what happened.”

Rudaw