Iran, six powers lock horns over nuclear reactor that could yield plutonium

Iran and world powers locked horns on Wednesday over the future of a planned Iranian nuclear reactor that could yield plutonium for bombs as the United States warned "hard work" will be needed to overcome differences when the sides reconvene in April.

The meeting in Vienna was the second in a series that the six nations - the United States, China, Russia, Germany, France, Britain - hope will produce a verifiable settlement on the scope of Iran's nuclear program, ensuring it is oriented to peaceful ends only, and put to rest the risk of a new Middle East war.

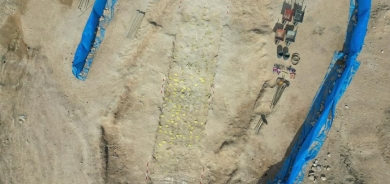

This week the two sides endeavored to iron out their positions on two of the thorniest issues: the level of uranium enrichment conducted in Iran, and its Arak heavy-water reactor that the West sees as a possible source of plutonium for bombs.

They appeared to reach no agreements and said only that they would meet again on April 7-9, also in the Austrian capital. However, Tehran's foreign minister voiced optimism that their July 20 deadline for a final agreement was within reach.

The broad goal is to transcend ingrained mutual mistrust and give the West confidence that Iran will not be able to produce atomic bombs while Tehran - in return - would win full relief from economic sanctions hamstringing the OPEC state's economy.

Iran denies that its declared civilian atomic energy program is a front for developing the means to make nuclear weapons, but its restrictions on U.N. inspections and Western intelligence about bomb-relevant research have raised concerns.

"We had substantive and useful discussions, covering a set of issues, including enrichment, the Arak reactor, civil nuclear cooperation and sanctions," European Union foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton told reporters after the two-day session.

The United States has called on Iran to scrap or radically alter the as yet-uncompleted reactor, but Tehran has so far rejected that idea while hinting it could modify the plant.

"We shared with Iran ideas that we have," a senior U.S. administration official told reporters condition of anonymity. "We have long said that we believe that Arak should not be a heavy water reactor as it is, that we did not think that that met the objectives of this negotiation."

Enrichment is also a sticking point in the talks. "It's a gap (on enrichment) that's going to take some hard work to get to a place where we can find agreement," the U.S. official said.

Enriched uranium can serve as fuel for nuclear power plants or, if refined to a high degree, for the core of an atom bomb.

As in past rounds of negotiations, the U.S. delegation, led by Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Wendy Sherman, held an 80-minute bilateral meeting with the Iranian delegation. Such high-level, face-to-face contacts between the long estranged countries - virtually unthinkable one year ago - have become almost "routine", according to the U.S. official said.

IRANIAN OPTIMISM

Western nations want to ensure that the Arak reactor is modified sufficiently to ensure it poses no bomb proliferation threat. Iran insists that the desert complex be free to operate under any accord as it would be designed solely to produce radio-isotopes for medical treatments.

"The Arak reactor is part of Iran's nuclear program and will not be closed down, (like) our research and development activities," Foreign Minister Javad Zarif told reporters.

Possible face-saving options that could allow Iran to keep the reactor while satisfying the West that it would not be put to military purposes include reducing its megawatt capacity and changing the way it would be fuelled.

Iran and the powers aim to wrap up a permanent accord by late July, when their trailblazing interim deal from November 24 expires and would need to be extended, complicating diplomacy.

Zarif voiced optimism about the talks. "At this stage we are trying to get an idea ... of the issues that are involved and how each side sees various aspects of this problem," he said.

A Western diplomat also said the purpose of the current round of negotiations was not to nail down a final agreement.

Asked whether he expected the negotiating deadline to be met, he said: "Yes, I do ... I am optimistic about July 20."

The sides are conscious that it may be hard to reach gradual deals without having the overall picture in sight and are insisting that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed".

Much of the progress so far has been achieved since last year's election of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, a relative moderate who launched a policy of "constructive engagement" to end Iran's international isolation.

"Our ultimate goal is to maintain our peaceful nuclear programs in line with international rules, and at the same time remove all concerns of the international community," the semi-official Fars news agency quoted Rouhani as saying. "So far we are satisfied with the results and hope that the whole dispute will be settled soon with goodwill of the other side."

Since Rouhani's rise, day-to-day relations between Iranian and six-power negotiators have greatly improved. Some senior officials now address each other by their first names and use English in talks, rather than going through onerous translation.

"Everybody is very professional, very serious, very focused. There are no histrionics, there is no walking out, there is no yelling and screaming ... People understand the stakes are pretty profound," the senior U.S. official said on Wednesday.

But gaps between expectations on both sides, and their own internal divisions, could still scupper diplomacy.

Both the U.S. and Iranian delegations - the two pivotal players in the negotiations - face intense pressure from hawkish critics back home. In Washington, a large majority of U.S. senators urged President Barack Obama to insist that any final agreement state that Iran "has no inherent right to enrichment under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty".

That would be a non-starter for Iran, which cites a right under the NPT to produce nuclear energy for civilian purposes.

The powers will also want to spread out the sanctions relief over years, or possibly decades, to ensure they maintain their leverage over Tehran and that it honors its end of the deal.

Iran has already suspended its most sensitive, higher-grade enrichment - a potential pathway towards bomb fuel - under the November accord and won modest respite from sanctions.

(Additional reporting by Justyna Pawlak and Louis Charbonneau; Editing by Mark Heinrich)

(Reuters) -